No, this is not a blog post about how to figure out if your electrician has connected your fuses, switches, and circuit breakers in the right way. Although, I recommend that you have one of those done by somebody who actually knows what they’re talking about in that dimension. This post is about the polarity in educational testing: there are those who hate it and those who appreciate it. I guess there are some who love it, but let’s not go overboard.

What would render public conversations about testing less controversial and disputatious? Is there a mode of interaction among people with different viewpoints about testing that would allow for “the possibility of disagreement without enmity”? That last phrase came at me from a New York Times Agnes Callard essay on Aristotle that also differentiated messaging from “literal speech” by defining the latter as “systematically truth-directed methods of persuasion — argument and evidence”. I think that phrase also describes good tests, but in making such an contention the possibility exists that I am crossing the line into what Callard describes as messaging: the “kind of speech that it would be a mistake to take literally… (Speech) that falls under the rubric of ‘making a statement,’ … words (that) exist to perform some extra-communicative task; in messaging speech, some aim other than truth-seeking is always at play.” In other words, my application of Callard’s phrase above with such loaded words as ‘systematically’, ‘truth directed’, ‘argument and evidence’ portrays tests as on the side of all of these objective (usually) valued dimensions.

That I grabbed Callard’s phrase as being synonymous with the intentions and actions of a ‘good test’ shows a particular cognitive bias at work; a kind of motivated reasoning to appropriate supportive material for my already formed and deeply entrenched belief that tests serve important purposes in our society and that movements against testing may cause harm to our world. That gets us back to the first question: what would render public conversations about testing less controversial and disputatious given our reflexive tendency to exhibit a confirmation bias, a favoring and highlighting of ideas and information congruent with our existing beliefs. People who hate testing will look for articles and posts that point to the deficiencies and even destructiveness wreaked by testing. People who espouse testing… Well, you know the answer.

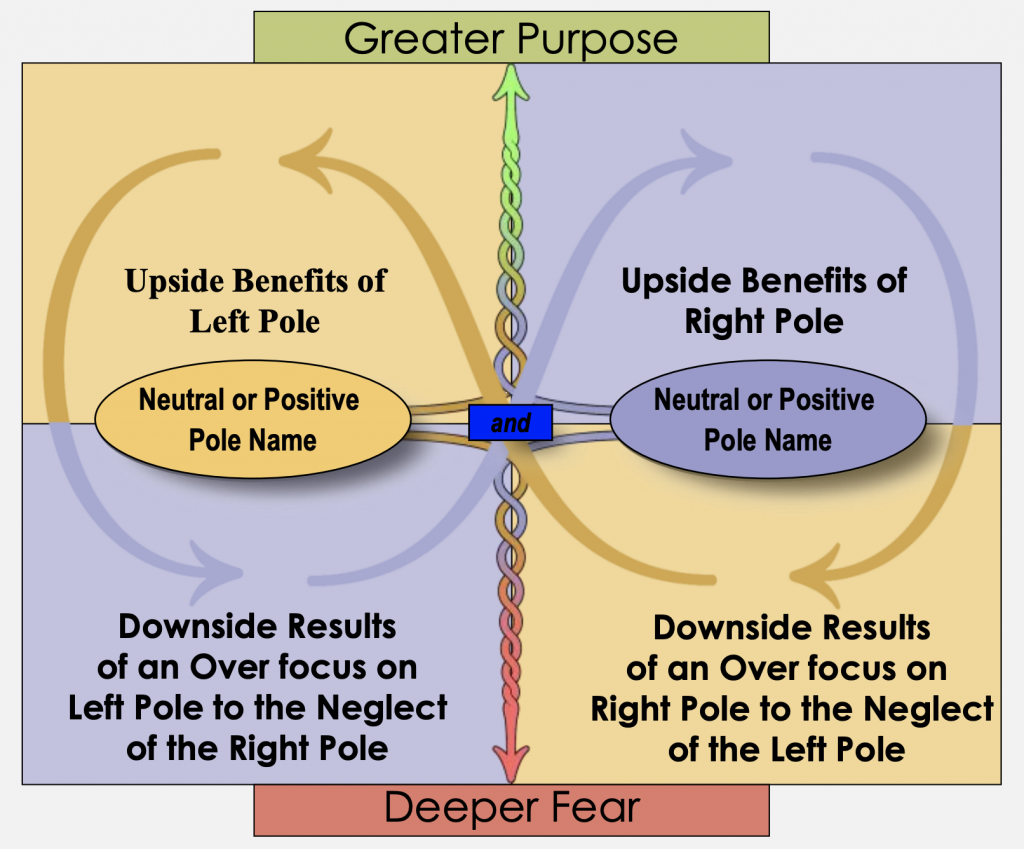

Perhaps one technique worth trying was taught to me by Barry Johnson during a session at Harvard Graduate School of Education Learning Innovation Laboratory some years ago. Barry has focused his work for decades on what he terms as polarity management. In working with groups, Barry came to see a significant difference between a problem that its members might face and a polarity. A problem is a situation that likely has a solution. A polarity (which we might also know as as “a paradox, conundrum, or contradiction — is a dilemma that is ongoing, unsolvable, and contains seemingly opposing ideas.” Barry made the point that polarities are interdependent pairs, “With all polarities—because they are interdependent—it makes no sense to connect them with ‘or.’ We need to connect them with ‘and.’“ Or think of it this way: “Polarities cannot be solved; they can only be navigated. And the way we navigate is not by choosing between, but by integrating both.” (From a nice thread on polarity on Twitter from Brian Stout)

In the case of testing, that would mean that the choice is not between the current regimen of testing and the current criticism of testing, but rather discerning a way of recognizing and acting upon their interdependency. If the testing dilemma is that some members of our society are experiencing the downside of one ‘pole’ — for example, the emphasis on teaching to the test, carving out resources such as time, money, and attention for the taking of tests, etc. then they come into conflict with those who insist upon the necessity for accountability, requirements for measurement, etc.

But simply moving toward the “testing bad’ or ‘testing good’ pole without a recognition that there is an inescapable polarity or paradox at play means that society can quickly experience the downside of any supposed solution—and before long, we will make another in a series of endless pendular moves to the opposite direction as a society. (A good video describing polarity management with Barry offerng his highly engaging explanations is at this YouTube link.)

In this personal history of testing, to insist that to get as close as possible to some truth about someone or some group we need testing would ignore the polarity. Nothing will change. Even when proponents of testing acknowledge that no one knows the absolute truth but with a good test we can avoid bamboozled by irrelevant noise or misled by spurious information, they still fail to persuade those clinging to the opposite pole. Similarly, decrying testing is not going to make it disappear.

Barry Johnson suggests a way forward — or perhaps I should say sideways. He notes that, “There’s a natural tension between the poles of a polarity, but it can be leveraged in such a way that it creates a virtuous cycle of energy lifting you towards a greater purpose.” (or vicious cycle of energy pushing towards a greater fear).” My take is that we have seen the vicious cycle of energy pushing toward a greater fear in public and private conversations about testing. What if we headed in the other direction? What if the first step was toward the other pole? Refrain from a continuation of the messaging about the value of testing and instead solicit the involvement of the other side in exploring the polarity. Here’s how Barry puts it more generally, “To make sustainable progress, key stakeholders will need to see the underlying polarity and commit to action steps supporting both upsides.”

What that means in the case of this particular blog readers to connect me with the critics of testing? Of course, I know enough of them that I can reach out on my own and even if they don’t participate personally I can cite their work. If you know someone who is a critic of testing on any level — PTA, teaching staff, college administration, policymaker — please help me to contact them so that I might involve those at the other pole in this effort.

Candidly, I am not as extreme in my support of testing as others. As already noted in a previous blog post, the kind of testing that I would like to see is the kind that I tried to support when at ETS: the sort of formative assessment that would eliminate our current summative tests, the kind that third-graders and seventh graders and others take. But I am pro-testing and I would like to connect with those who seriously are protesting testing. Reply here or send me a private message to help me connect. And, yes, I’m ‘messaging’ (as Agnes Callard would put it) right now if you’re wondering.

Great reminder of the distinction between a problem (to be solved) vs a dilemma (to be managed). It took a long time for me to recognize the difference.

I’m still working on it!