Why spend precious time discussing the harmless MBTI? My purpose is not to try and change people’s minds about that device. Goodness, how could anyone have the presumption to try and alter opinions anything these days?

I love this quote on that point from the author of cognitive dissonance theory, Leon Festinger ( When Prophecy Fails , 1956) that I think is as true of me as anyone else:

“Suppose an individual believes something with his whole heart; suppose further that he has a commitment to this belief, that he has taken irrevocable actions because of it; finally, suppose that he is presented with evidence, unequivocal and undeniable evidence, that his belief is wrong; what will happen? The individual will frequently emerge, not only unshaken, but even more convinced of the truth of his beliefs than ever before. Indeed, he may even show a new fervor about convincing and converting other people to his view.”

Thus, regarding the importance of reliability and validity, the passion of the convert, the pilgrim, even the zealot, drives me to advocate for those principles to be used in the service of learning. Crane Brinton, the great historian of revolutions understood “that in all the social sciences genuine scientific detachment is difficult to attain, and in any “absolute” or “pure” sense impossible of attainment.” The desire “to prove a hypothesis or a theory of one’s own may bring to the distortion or neglect of facts some of the most powerful sentiments in human beings.” No matter how much we’d like to see things change like the way personality tests are used in constructed or the prevalence of summative assessments over formative ones, one of the first precepts of initiating change is to engage and listen to the resistance — to those people who are on the so-called ‘other side’. Thus, hearing and reading others’ opinions on these topics helps a great deal. So have at me. Meanwhile, here’s the rest of my story with the Myers-Briggs.

I was surprised upon arriving at ETS in 2001 to discover that the creators of Myers-Briggs had at one time been resident on campus and involved in developing the test as a possible component of the organization’s offerings. Twenty years ago, I didn’t know that ETS conducted a great deal of research from its earliest days on Cognitive, Personality, and Social Psychology. This paper by the late Nate Kogan recaps a fascinating strain of research done there on creativity. But one day in the course of the many inquiries I made trying to learn the history of the place, one of the testing veterans told me that not only had Myers-Briggs been on campus in Princeton but that we had “kicked them out.” And all of the top research people who told me about this did so with pride!

I kept chasing the story down and eventually learned that Larry Stricker, one of our longest-serving and most highly published researchers, had been the broom that swept poor Isabel Briggs (supposedly in tears) from the promised land of ETS. In my last job at ETS for over two years as a Knowledge Broker in the R&D division, the chances of running into Larry increased markedly and I managed to interview him on the subject. This event of kicking out the MBTI had at this point occurred over 40 years earlier and Larry still retold the sequence gleefully.

Researchers have their own particular sense of humor.

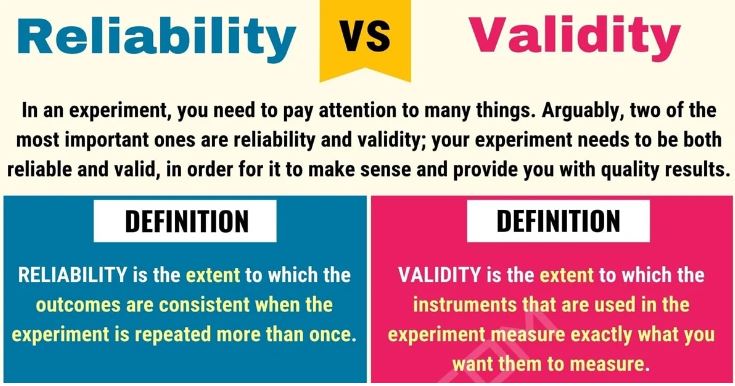

Larry was on a team that had the responsibility for investigating the reliability and validity of MBTI, a test that its creators conceived originally at the beginning of the 20th century. Henry Chauncey, the founder of ETS, believed that the organization should branch out from its work on the SAT and GRE to other directions. Myers-Briggs seemed like an easy and lucrative acquisition. Thus the invitation he issued to Isabel Briggs with the expectation that folding the test into ETS would just be a formality. But Mr. Chauncey though astonishingly talented and visionary was not a psychometrician. The researchers in those early days of ETS believed as today that each one of their tests should meet the highest standards of validity and reliability; in other words, those taking the test should get a result that would be an accurate measure of what was being tested and they should feel confident that if they took the test a couple of months later the result unless there was some sort of intervention would be pretty much the same.

Merve Emre writes in The Personality Brokers how Larry “Stricker, in secret, was preparing a memorandum addressed to the ‘graybeards’ in the research department that attempted to outline ‘the major problems in the” MBTI. Emre notes that Briggs would go from dislike of Larry to hatred; “… At her home office in Swarthmore, she kept a secret file on his activities titled ‘Larry Stricker, Damn Him’.” Henry Chauncey would write in a memorandum of a conference with Isabel that occurred on May 3, 1961 that Larry had succeeded in blowing up any chance of MBTI being part of the ETS portfolio. Briggs would complain that she had been “blindsided” by the report and that it was full of “misinterpretations, distortions, and omissions.” But 40 years later when I arrived at ETS all of the researchers still stood by that decision.

Why? Larry’s work uncovered significant flaws in the test, flaws that still exist today. In fact, the MBTI folks seem to know this themselves: they withdrew their test from the employment market to avoid the kinds of lawsuits that come from offering an assessment lacking in validity. When Stricker delivered his report, the scientists were stern in their rejection. Hence the report perhaps apocryphal as to the tears of Isabelle Briggs. But even if it was true, she cried all the way to the bank. Even today with numerous competitors that didn’t exist at the time of her banishment, Myers-Briggs has revenues in excess of $50 million with only a few hundred employees.

There is a postscript to Larry’s story: Merve Emre who is a regular writer at the New Yorker contacted ETS for some background for her book but she mostly got the story wrong and in her last chapter she definitely forgives, even defends the deficiencies of MBTI, which is too bad because there’s a finite amount of resources available for testing and having people use an assessment with these kinds of weaknesses constitutes squandering. Larry Stricker asked the publisher of the book to make corrections, but to no avail. Maybe that’s the ultimate judgment on how validity and reliability matter: people, even those in authoritative positions at institutions like publishers, just don’t care about them as much. What will that mean for us all going forward? Too big a question for me in this venue but…

In Part IV (which was originally just supposed to be 2 posts, but go figure) I will share my encounters with a cohort of tests that offer validity and reliability when it comes to taking a look at certain of our attributes. In the meantime, please do comment!

Thanks for fleshing out the MBTI/ETS connection. I too had heard about the history but never heard the full story!

There’s even more to the story which Larry told me. He relished his role. I once asked Michael Zeiky if he regretted MBTI leaving ETS and with his characteristic bluntness, he stated, “absolutely not!”

Pingback: Myers-Briggs Antipathy: Maybe It’s Just My Personality–Part II – Testing: A Personal History

Pingback: Myers-Briggs Antipathy: Maybe It’s Just My Personality – Testing: A Personal History

Pingback: Myers-Briggs Antipathy: Maybe It’s Just My Personality Part V – Testing: A Personal History