Two questions

- Success at what exactly?

- Will my answer change the mind of anyone already biased for or against the test?

As stated in yesterday’s entry in this marathon of blog posts on various aspects of testing and how they’ve intersected with my own personal history, I do NOT think the SAT matters as much to the workings of our world as others do. By others, I mean the people who keep writing about it, the parents who keep complaining about it, university administrators who keep equivocating about it. But before I steer the SAT out of this stream of my altered consciousness, there is some value in answering the first question because also as noted yesterday the attacks against the SAT are in many instances attacks against testing educational measurement in general. And such attacks are notably bad phenomena in our society.

During my years at ETS, I didn’t have as much contact with the College Board as my fellow officers did. However, I did get to participate in strategic discussions for the corporation especially as the CB leadership again and again threatened to take away the work that ETS did on the tests. One meeting not long after I had been named Associate Vice President of Human Resources in addition to my Chief Learning Officer responsibilities raised the possibility of ETS creating tests that would compete with the College Board. Two other senior officers and myself (incidentally also combative middle-aged males) were very much in favor of pursuing that direction, but both sides backed away from a divorce at that time. Before I came to ETS, there was an agreement to merge the two organizations but the leadership of ETS backed away at the last moment. A former senior officer of ETS once described the relationship the two organizations as Siamese twins that never should’ve been separated at birth. But they were separated with ETS becoming a sort of all-encompassing service bureau to the CB. Putting them back together meant that the question that will come up again and again with any merger proved the sticking point: who was going to be in charge of the combined operation? ETS in its revenues is significantly larger than the College Board and has a number of other different tests. Additionally, ETS is the world’s greatest center of research on educational measurement and the College Board is not even in the same ballpark in terms of number of researchers or quality of scientists. But the College Board had the customers, which matters a great deal in any business.

Because such a merger will divorce never happened, there was an enormous amount of redundancy as the years went by with a lot of wasted checking the checkers activity. This context matters because I observed both ETS and the College Board miss many opportunities over the years to better serve test-takers and institutions. Unsurprisingly, my take is that the CB missed more chances than my team did, but that’s just my opinion and opinions are like noses everybody has one. What are not opinions and much more pertinent to answering our first question at the start of this entry are the findings of various researchers that they don’t agree about whether the SAT or even scores on AP tests predict grades in college or graduation rates within six years. One of the most comprehensive analyses ever done on this subject was by Bowen, Chingos, and McPherson. They concluded that “a judicious combination of cumulative high school grades and content-based achievement tests (including tests of writing ability) seems to be both the most rigorous and the fairest way to judge applicants.” Notice the mention there is of ‘AP tests’ and not SAT scores.

But I have no idea what difference it really makes to keep on harping about looking at GPA instead of test scores because as Sanchez and Mattern discovered in their research most of the kids with high test scores also have high GPAs and most of the kids with “poor high school grades tend to earn low test scores.” And they assert that “Evidence of the predictive validity of college admission measures is clear: both HS GPA [high school grade point average] and admissions test scores, such as the ACT and SAT, are positively correlated with a variety of college outcomes, such as enrollment, first your grade point average, persistence to the supper year, degree completion, and on-time degree completion.”

That gets us to a kind of an answer to our first question: the SAT by itself or along with other measures can predict fairly well success at getting in and getting on with college. Those tests certainly do better in predicting all of those outcomes than a lot of other highly wanted alternatives to testing. As Sackett and Kuncel found, “other research on alternative admission measures has been disappointing.” They go on to talk about something called the noncognitive questionnaire that “demonstrated near zero relationship with academic outcomes in a meta-analysis” and Sternberg’s Rainbow Project, “which produced a mixture of scales with zero criterion related validity and some that did demonstrate useful correlations. However, the latter also tended to produce very large racial and ethic differences, even though they were less reliable than other assessments and some claims of success were, in fact, based on trivial sample sizes…” You get the idea: it’s hard to make a really good admission tests because human beings are complicated.

(BTW all of the references thus far in tis post are from the book Measuring Success that was the source of a previous quote from Emily Shaw that bears repeating: “decades of research has shown that the SAT and ACT are predictive of important college outcomes, including grade point average (GPA) [in college], retention, and completion, and they provide unique and additional information in the prediction of college outcomes over high school grades.” Emphasis added and the same book contains research that disagrees. There is the frustration of working with psychometrician’s and other educational measurement researchers: you’re unlikely to find strict agreement on any subject

But do the SAT and other admission tests predict success in life? Some admittedly prejudiced SAT prep vendors like this one think so and thus quote this research by Lubinski et al: “individual differences in general cognitive ability level and in specific cognitive ability pattern (that is, the relationships among an individual’s math, verbal, and spatial abilities) lead to differences in educational, occupational, and creative outcomes decades later.”

But does the name Lubinski sound familiar to you? He was cited in our blog just yesterday as co-author with my former colleague Harrison Kell of a paper that argues vigorously for “the incorporation of spatial ability into talent identification procedures and research on curriculum development and training, along with other cognitive abilities harboring differential—and incremental—validity for socially valued outcomes beyond IQ (or, g, general intelligence).” [Emphasis added]

Considering that 2nd quote it looks doubtful that Lubinski would agree with the generalization made by the SAT prep sales site. Laypersons tend to overgeneralize the results from one particular paper. We all tend to ignore conflicting results that bump up against our view of how the world operates. And we conflate a positive correlation between two elements like IQ and career success with a certainty.

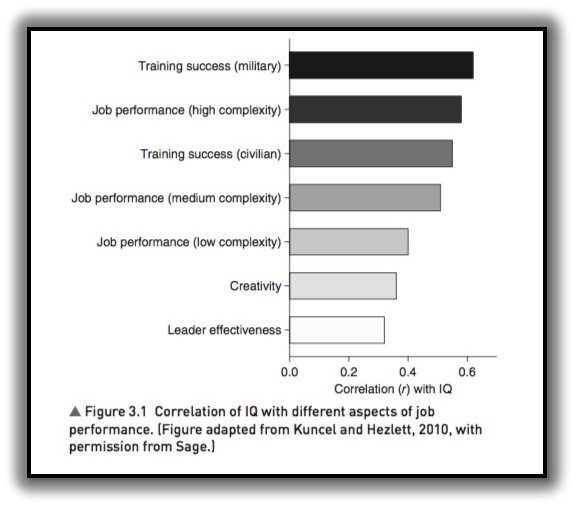

Brian Resnick in Vox gives a nice example of such correlations and how they can confuse:

Like mortality, the association between IQ and career success is positive. People with higher IQs generally make better workers, and they make more money.

But these correlations aren’t perfect.

Correlations are measured from -1 to 1. A correlation of 1 would mean that for every incremental increase in IQ, a fixed increase in another variable (like mortality or wealth) would be guaranteed.

Life isn’t that pretty. Many of these correlations are less than .5, which means there’s plenty of room for individual differences. So, yes, very smart people who are awful at their jobs exist. You’re just less likely to come across them.“

But let’s take a look at the chart that accompanies Resnick’s article to understand what is meant by these correlations and why they get misinterpreted.

First the version in the article of the chart:

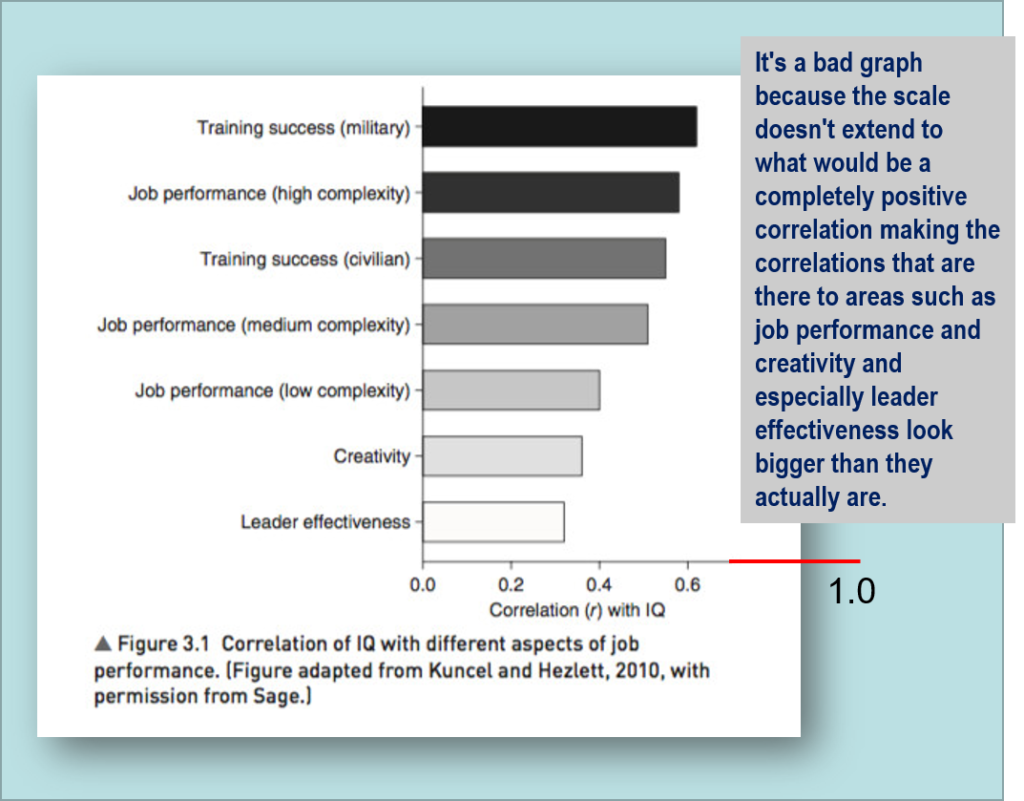

It looks like these are pretty good correlations. But now take a look at this one that I edited and discover again why a ‘positive correlation’ is NOT a sure thing

What do we mean by success? Consider the LSAT. It likely predicts how well you going to do in law school, but it doesn’t protect necessarily how good a lawyer you will turn out to be.

From the previously referenced Malcolm Gladwell article. ”…there’s no reason to believe that a person’s L.S.A.T. scores have much relation to how good a lawyer he will be. In a recent research project funded by the Law School Admission Council, the Berkeley researchers Sheldon Zedeck and Marjorie Shultz identified twenty-six “competencies” that they think effective lawyering demands—among them practical judgment, passion and engagement, legal-research skills, questioning and interviewing skills, negotiation skills, stress management, and so on—and the L.S.A.T. picks up only a handful of them. A law school that wants to select the best possible lawyers has to use a very different admissions process from a law school that wants to select the best possible law students.”

I hope that I’ve shown how these arguments about what the tests measure in terms of success and even what success is supposed to be will likely go on forever. But they won’t endure in this blog because we will turn our attention over the next several days to a much more important topic: our test scores simply a product of our genetic inheritance? See you tomorrow.

Just a brief comment from me today: I loathe any kind of truncated scale on a graph or chart. I find them trickier to interpret and I am quite data savvy, so wonder how others less clued in might construe them. It is bad enough to see them in academic papers per se, but when they get picked up by the media and edited or re-presented by people who really don’t understand them, the problem is magnified. How is a layperson supposed to understand correlation (or lack of correlation) if the data is presented thus?! Of course the cynic in me wonders if such misrepresentation could possibly be deliberate.

Pingback: My Blue Genes – Testing: A Personal History

Pingback: Are Problems With Tests Really Problems With Authority? – Testing: A Personal History