My gratitude swells for the generosity of Marianne Talbot who has commented on each of the January jolt posts thus far. But in an echo of my last post, it’s not just the quantity of her comments but the quality that matters as she offers insights and resources. In a recent comment, Marianne offered this idea: “Completely agree that the truth for the test-taker is always different to that for the test-setter and the test-marker etc etc etc, all the way up to the Secretary of State for Education, via the test-taker’s teacher, their parents, their prospective university department… This multiplicity of truths echoes the multiplicity of test purposes identified by Paul Newton — it depends on who’s asking!”

The abstract of the paper at the link above is all that can be obtained, but if you go to ResearchGate it’s possible to request the full PDF from Paul. However, over at ERIC, Paul authored a different paper that is available as a free full text and happily fits our subject of today’s post: validity. The paper from 2016, The Five Sources Framework for Validation Evidence and Analysis, addresses at least a practitioner if not professional in educational measurement audience, but you can derive two important aspects of validity just from the very beginning of the paper:

- what matters most in a test is its validity

- how professionals get to establishing the validity of a test is pretty darn complicated and even disputed

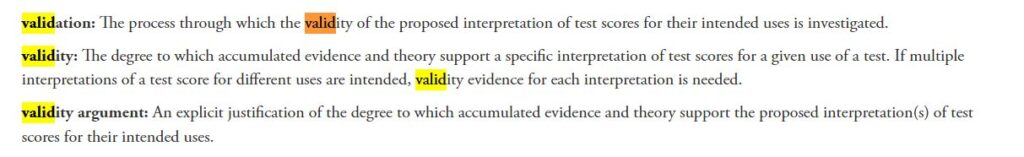

Additionally, Paul argues that there may be flaws in that standard framework for thinking about evidence for the validation of a test. It’s a really worthwhile paper, but my intentions today are more basic: I want to talk about validity in test scores; here’s a link to a glossary from NCME and below is a screenshot of the relevant terms at that VERY useful site.

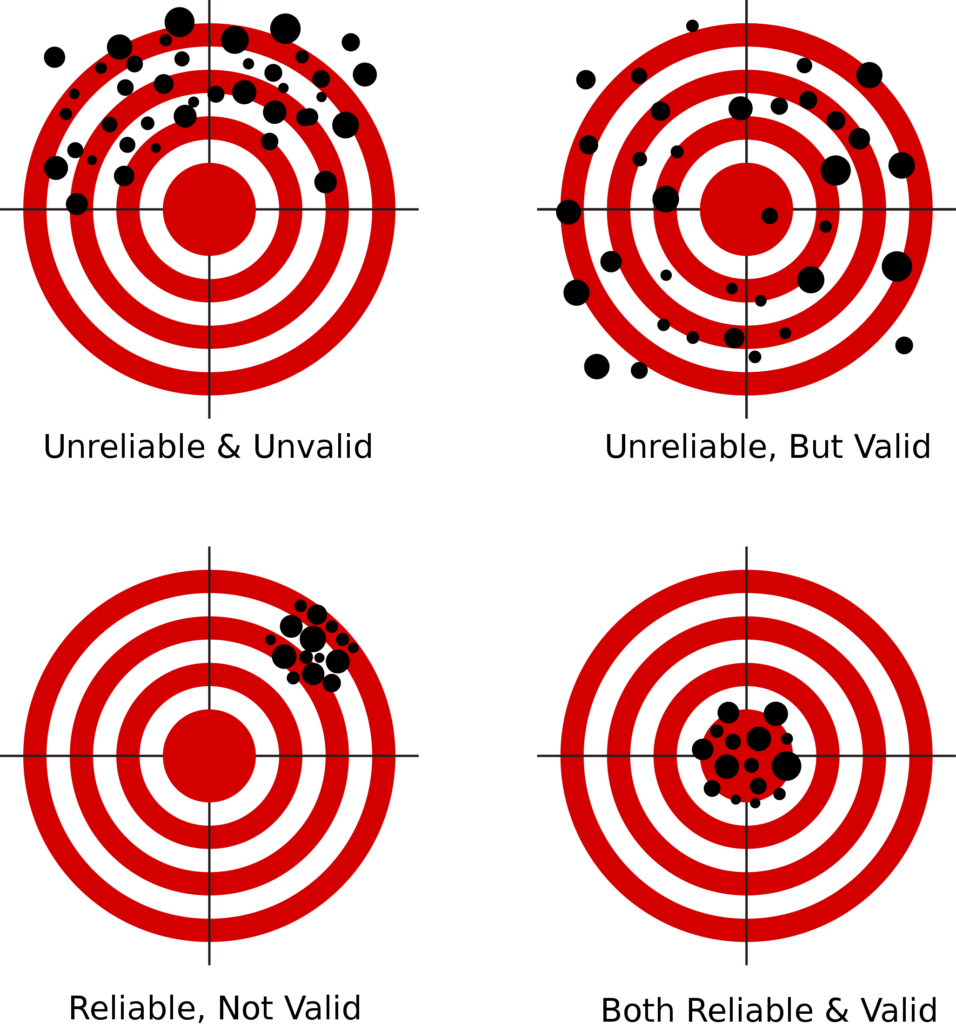

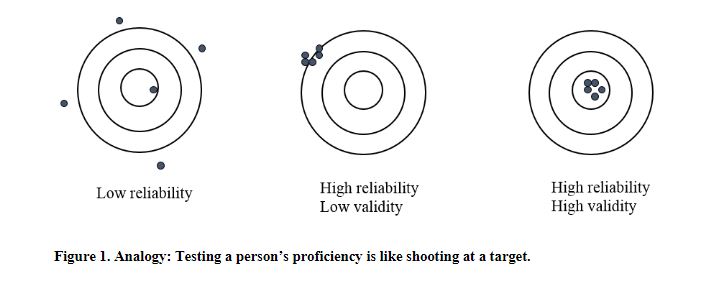

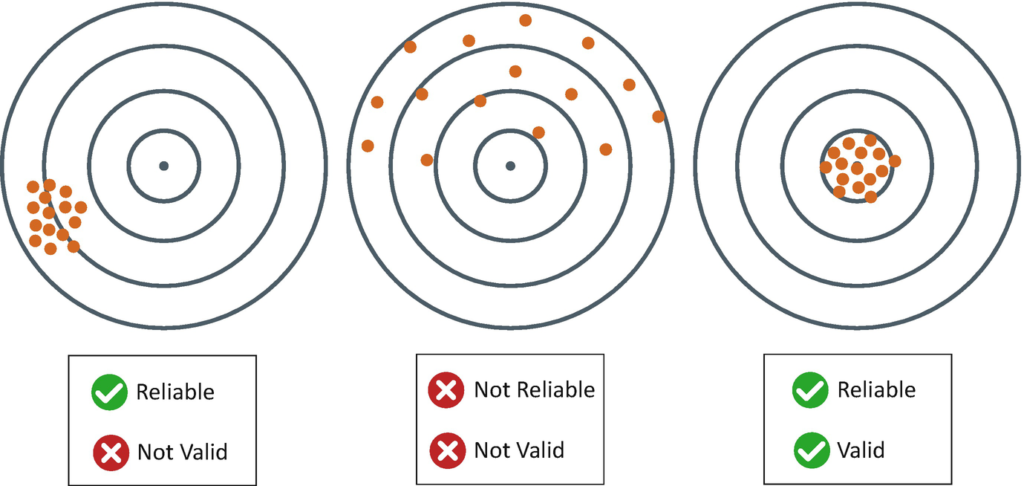

At ETS, the three most important aspects of the test — and of our professional lives!!! — were validity, reliability, and fairness in that order. Obviously, some former colleagues would argue that they were equal in their importance, but by definition if the test is invalid then it will be also unfair in any form or accommodation. Recognizing that these three were the cardinal principles of the couple of thousand people that I was going to be working with when I arrived at ETS in 2001, I delved into any material available on what validity means. But as a stroke of immense luck, one the first ETSers and I came to know was Michael Zieky. His presentations in teaching on the basics of assessment were prized and famous among ETSers. Early in my time there in Princeton, I attended a presentation where Zieky using an overhead and transparencies showed an archery target. Here’s a reproduction of that illustration from a paper by Skip Livingston.

Zieky displayed a marvelous pithiness to many of his definitions in these lectures. Here is validity:

“The test is doing the job it was designed to do. The test is working as it should. The scores are valid for the intended purpose.”

You want something more technical? Okay

Here’s Zieky’s definition

- “Validity is the extent to which inferences & actions made on the basis of test scores are appropriate and supported by evidence.”

And Sam Messick’s definition, which is probably the most celebrated sketching of the concept:

“Validity is an overall evaluative judgment of the degree to which empirical evidence and theoretical rationales support the adequacy and appropriateness of interpretations and actions on the basis of test scores or other modes of assessment (Messick, 1989b). Validity is not a property of the test or assessment as such, but rather of the meaning of the test scores. These scores are a function not only of the items or stimulus conditions, but also of the persons responding as well as the context of the assessment. In particular, what needs to be valid is the meaning or interpretation of the score; as well as any implications for action that this meaning entails (Cronbach, 1971).

Here’s a funny one from Paul Kline:

“A test is said to be face valid if it appears to measure what it purports to measure, especially to subjects. Face validity bears no relation to true validity and is important only in so far as adults will generally not co-operate on tests that lack face validity, regarding them as silly and insulting. Children, used to school, are not quite so fussy.” Paul Kline, 1986 book A Handbook Of Test Construction: Introduction To Psychometric Design

And if you want me to get fancy, I can give you a wonderful two sentence pas de deux offering from Harold Gulliksen that relates validity to its sibling, reliability.

“Reliability has been regarded as the correlation of a given test with a parallel form. Correspondingly, the validity of a test is the correlation of the test with some criterion.” (Gulliksen, 1950, p.88)

Get it? Reliability happens if different versions of the same test give you the same score within a reasonable margin, but validity is whether that score tells you accurately what somebody knows or can do in a particular area like dishwasher repair or cybersecurity or hair dying. There are tests for all of those jobs and the people taking them probably have some sort of a belief that those tests are valid, that they fit these definitions above.

But for our purposes, these definitions may prove to be an obfuscation. When I think of validity, I think of that archery target and an arrow smack dab in the middle, a score that tells me what someone knows or can do relative to a particular construct. Or as Michael Zieky said: “The test is doing the job it was designed to do. The test is working as it should. The scores are valid for the intended purpose.”

Although such questions as to whether a test score is valid are seen as the responsibility of those behind the scenes in education departments, academic institutions, and psychometric organizations, wouldn’t a more vigorous dialogue about the validity of tests used benefit everyone? At one point many years ago, I was speaking to one of our executives about logistical and operational problems with a particular examination. He lamented all of the hassles that were being visited upon ETS as a result of a conga chain of snafus. And then throwing his hands up in the air, he moaned, “And I’m not even sure this test is valid!” I was shocked. Here we were all running around trying to fix things in the delivery and scoring of this examination and looking like what my mother used to describe as ‘chickens with our heads cut off’, and the test wasn’t even going to do the job it was designed to do for the kids who were the test takers, for their teachers, for their parents? Yep. Nobody in the general public seemed to know that there was any doubt about its validity and I didn’t know enough about this particular examination or validity to be able to make a judgment. But that such a concern could be voiced seemed pretty important; certainly, more important than knowing where a carton of completed tests had escaped the supply chain at that particular moment. And that brought to mind a very different definition of validity from George Kelly:

“Validity is a matter of the relationship between the event as it happened and what the person expected to happen.” Read ‘event’ as test, examination, assessment, whatever you want to call it. Read ‘person’ as the test-taker and that means that validity requires that person have gotten what they thought they were going to get out of taking the test. Those testtakers in the exam mentioned above all expected to get something out of taking that test. Did they get it? Kelly continues with this alternate definition:

“More correctly stated, (validity) is the relationship between the event as he construed it to happen and what he anticipated. It is in this relationship between anticipation and realization that the real fate of man lies. It is a fate in which be himself is always a key participant, not simply the victim.”

How many people are victims of inadequate or inaccurate validity in the tests to which they are subjected? The vaunting of GPA or Grade Point Average as a ‘better’ indicator for admission to higher education then various standardized tests like ACT or SAT never seems to be interrogated on the reality that those grade points come in large measure from… tests, little pop quizzes, end of term exams, classroom questions. Were those assessments valid? This is a inquiry for which I would love to get some more stories and I will be reaching out to individuals to try to coerce… errr… beg them to contribute. Have you ever been involved with a test either as the person giving it or the person taking it where you thought that the score derived from test might not be valid? I know I have and more than once. I’ll share those stories in tomorrow’s post.

Thanks for the name check! I am enjoying reading and responding to these blogs – quite the new year’s jolt, as you intended. I am fascinated by the general lack of understanding (or even interest) of validity in relation to assessment – in the general public mainly, but also sometimes in the teaching profession (including university lecturers – wouldn’t you think assessment professionals would know better/be curious?). I use the archery target in my seminars on validity and reliability; it’s a very useful visual way of explaining the issue, and also of explaining that interpretation and inference are key to analysing any test responses/scores. But I suspect that although some assessors would struggle to identify why an assessment is not valid, the test-takers would likely know instantly – the assessment is probably asking them about stuff they haven’t been taught and/or asking them in such a way that they cannot understand what they are being asked! Perhaps I am in an especially cynical mood today, and yes, at a technical level, of course validity is complex and complicated, but at the most basic, moral level, it’s really simple – does the test assess what it is supposed to assess in a way that is fair and reliable? I realise this paraphrases the several definitions quoted above, and can be unpacked in a plethora of ways but it remains a mantra for me and my students, that I return to time and time again.

Pingback: When a bad test was good for… me – Testing: A Personal History