Part I

In our play, The Oracle, which ran off Broadway at Theater For the New City this past May, Joe Queenan and I had one character demolish her colleague in an argument thusly: “…But you’re not for me. Not my type. Type! Did you ever take Myers-Briggs? Because, Jesus, you are the poster boy for ENTJ. And the “J” is for Jerk!”

Okay, that’s not really what the J stands for, but I do think that personality tests like the MBTI often tend to jerk us around as to whether they offer anything useful. I’m about to embark upon two longer writing projects: an umpteenth draft of a play I first started over a decade ago and a new section of this website that will focus on tools to use in the big test that we call ‘work’.

Therefore, I wanted finally to write about this subject which has been hanging out in my folders as a collection of links and notes for a while. My 30 posts in 30 days on Testing: A Personal History never got to these stories. And they should be told because so-called personality tests have enormous influence in our society yet often lack the standards that we have associated with other kinds of assessment

Consider a test in which subjects are asked to react to various combinations of words and images, and their reaction times are measured, This assessment is the Black-White Implicit Association Test, a chief diagnostic tool of diversity training. Is it valid and reliable? No, according to Ulrich Simmack of the University of Toronto who has looked at this whole category of tests rather rigorously. But what was more concerning was that the test’s very creators don’t think it’s valid: “Tony Greenwald, a University of Washington researcher who co-created the test with Mahzarin Banaji at Harvard, conceded this point, telling … that the IAT is only “good for predicting individual behavior in the aggregate, and the correlations are small.” See this Vox story for more

But somehow this test like many other noncognitive assessments has become acceptable. Its goal is very worthy; implicit racism continues to be a significant problem in our society. Yet using a very poor test in that effort will not change things other than making the very people important to reach skeptical about any movement to identify implicit racism.

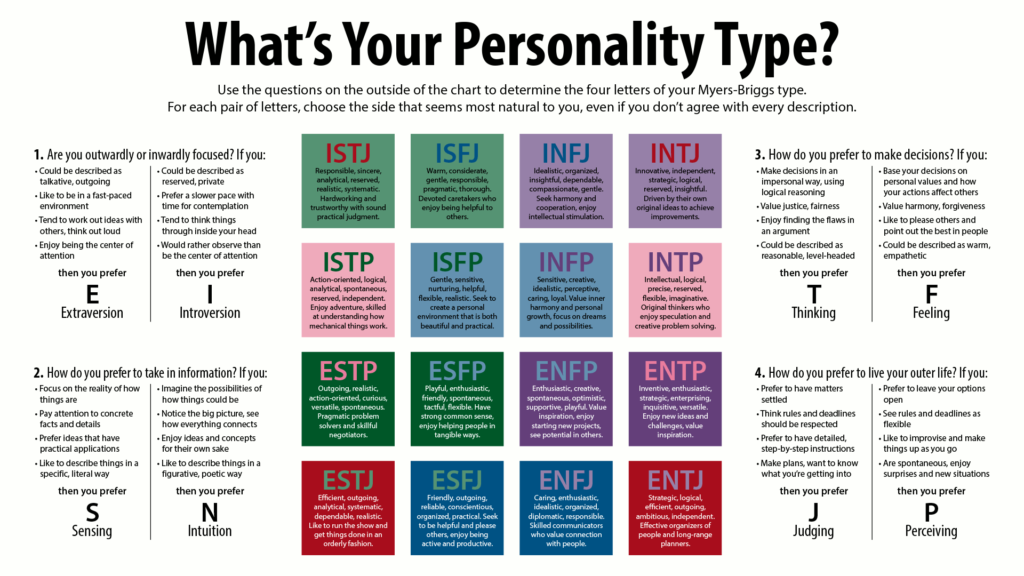

Like Pop in Moonstruck, I’m confused as to our acceptance of faulty tests. (Okay, the longer version of ‘I’m confused’ is here for those of you who foolishly have never seen this movie.) Yet this phenomenon of encountering so-called psychological tests that lacked basic validity and reliability occurred repeatedly as I lived in the world of testing. Consider the big one: Myers-Briggs. People love the Myers-Briggs. This article — What Personality Are You? How the Myers-Briggs Test Took over the World — from The Guardian documents the MBTI’s popularity while reviewing a fairly recent book by Merve Emre on it without delving into the inconsistencies and incompetencies.

We have known for over fifty years that MBTI is a very poor test for predicting or describing anything other than our appetite for labels. See this link on its atrocious reliability: “If you retake the test 30 days later, 50% of people change type!” One of the great advantages of working at ETS especially in my latter years in R&D was that I got to know and like Larry Stricker who was the very psychologist who initially debunked Myers-Briggs as a test; his work might explain why MBTI officials (as Louis Menand pointed out in this New Yorker article ) “do not refer to their device—a ninety-three-item, a-or-b format questionnaire that subjects are not supposed to take a lot of time filling out—as a “test.” The MBTI is not something you can pass or fail. The MBTI is an “indicator,” and what it is meant to indicate is the type of personality you have been born with.”. Hmmmm! It’s supposed to indicate the type of personality you were born with, but if a person takes it thirty days later it’s going to indicate a different personality? More on Larry’s initial debunking of the test further down.

MBTI may be the most annoying personality test, but is not the only one that falters. Theodor Adorno’s F-scale aimed to identify fascism and authoritarian personality but failed horribly. But people got the message on its inadequacies in less than five years. MBTI is still being used all over the place almost 90 years after its copyright.

My history with this test that predates my time in the testing industry. When I was an organizational consultant working with groups seeking to be more effective or innovative or whatever, one of the gimmicks employed was to give some sort of test that would identify the attributes of the group both at an individual and aggregate level. Then the group could decide whether something was missing or in conflict. (The person paying us to do the work had already told us their version of the problem, but it’s best to check what the group members have to say. It’s not usually the same answer.)

MBTI was an easy and inexpensive tool to employ. However, very quickly in my use of this assessment, I became suspicious of how many times individuals boasted of results that confirmed their extraversion. How could it be that they were all testing out as extroverts, people who preferred to get their energy from being in social situations? Experimenting subsequently on several groups, I asked participants first to write a short essay that described the perfect weekend. The responses demonstrated clearly attributes that were the opposite of extraversion; e.g., “just put me in a cozy cabin in front of the fire” or “hiking the Appalachian Trail with nobody else in sight!” As I pointed out these discrepancies after they took the test and got their skewed scores, there was often a great deal of embarrassed laughter all around. But they still wanted the ‘good’ labels.

Of course, that is humorous. But there’s a dark side to personality tests. One critic in the article at that link also from The Guardian states the case mildly, “…Personality tests are useful for individual people sometimes on journeys of self-discovery. But when they’re used to make decisions by other people affecting someone’s life, they become dangerous tools.” Tomorrow, in Part II of this rant, I’ll tell more of the story of how ETS kicked Myers-Briggs out of the organization and present some ideas about how tests of noncognitive attributes can be tests for learning. Remember: No Tests but for Learning!

Pingback: Myers-Briggs Antipathy: Maybe It’s Just My Personality Part IV – Testing: A Personal History

Pingback: Myers-Briggs Antipathy: Maybe It’s Just My Personality–Part III – Testing: A Personal History

Pingback: Myers-Briggs Antipathy: Maybe It’s Just My Personality–Part II – Testing: A Personal History