A Mystery Story Series

How Much Control Do We have Over Our Lives Anymore? And Do We Care?

Is it the Internet? Part 1

Detective stories always appealed to me. Hardy Boys books were often a quarter or less at the used books dealer in the tented emporium known as Frankie’s Market in North Jersey, a frequent destination for my bargain-hunting mother on Saturdays in the late 1950s. I collected the entire set of Tom and Frank (and Callie and Iola) before the age of 13. I once traded a complete Edgar Allan Poe for a complete Sherlock Holmes because the latter was ALL detective stories.

And like Holmes, those mysteries interest me the most whose presence in plain sight goes unrecognized by most people. Mysteries are tests of our perception, reasoning, and even imagination. In line with my everything is a test motto I started seeing if I could make sense the forces that compelled more people to vote for the current President-elect than for the current Vice President. One reason for this fascination is that I think the force in question may be even more pervasive and powerful than in this electoral role. I suspect that whatever caused this result — let’s term it the authority — claims a great sway over the lives of many fellow citizens. And so, I commence this series in which I try to discover what commanded certain choices. In the spirit of the early detective novels, let’s paraphrase Alexandre Dumas Pere, “cherchez l’autorite!!

Why authority? Does it fit the phenomena of voting, which we usually ascribe to an individualistic choice? Yes, if we latch onto one particular definition of the word that according to OED has been knocking around the English language since 1393: “Power to influence the opinions of others, esp. because of one’s recognized knowledge or scholarship; authoritative opinion; acknowledged expertise.“

What sources of authority in our lives were the decisive influences in this election?

Government? Corporations? Political Parties? Influencers? ‘Old’ Media? New Media?

I cannot even hazard a general answer as my own experience (indeed my whole life) is that of an outlier.

But as in those wonderful policiers, we can examine each ‘suspect’, and starting with the Internet fits the mood of the moment in many places but especially on the… Internet.

Round up the MOST usual suspect: The Internet

Many pundits (of which there are perhaps too many) and even just casual social media commentators ascribe to the Internet vast influence in our most recent election. Curiously, they tend only to look at its influence upon DJT voters, but that’s where we want to go anyway. According to this narrative, the decision to vote for Donald Trump in 2024 was due in part to information (and misinformation) that flowed to certain constituencies in an authoritative fashion via social media platforms, email campaigns, television advertisements (increasingly received digitally rather than via broadcast), and various video platforms like TikTok.

Can the internet or the even broader entity of digital media be considered an authority? Again consider that definition cited above: “Power to influence the opinions of others, esp. because of one’s recognized knowledge or scholarship; authoritative opinion; acknowledged expertise.” This seems to be the very accusation made by many observers: the internet in its various forms made people vote the way they did.

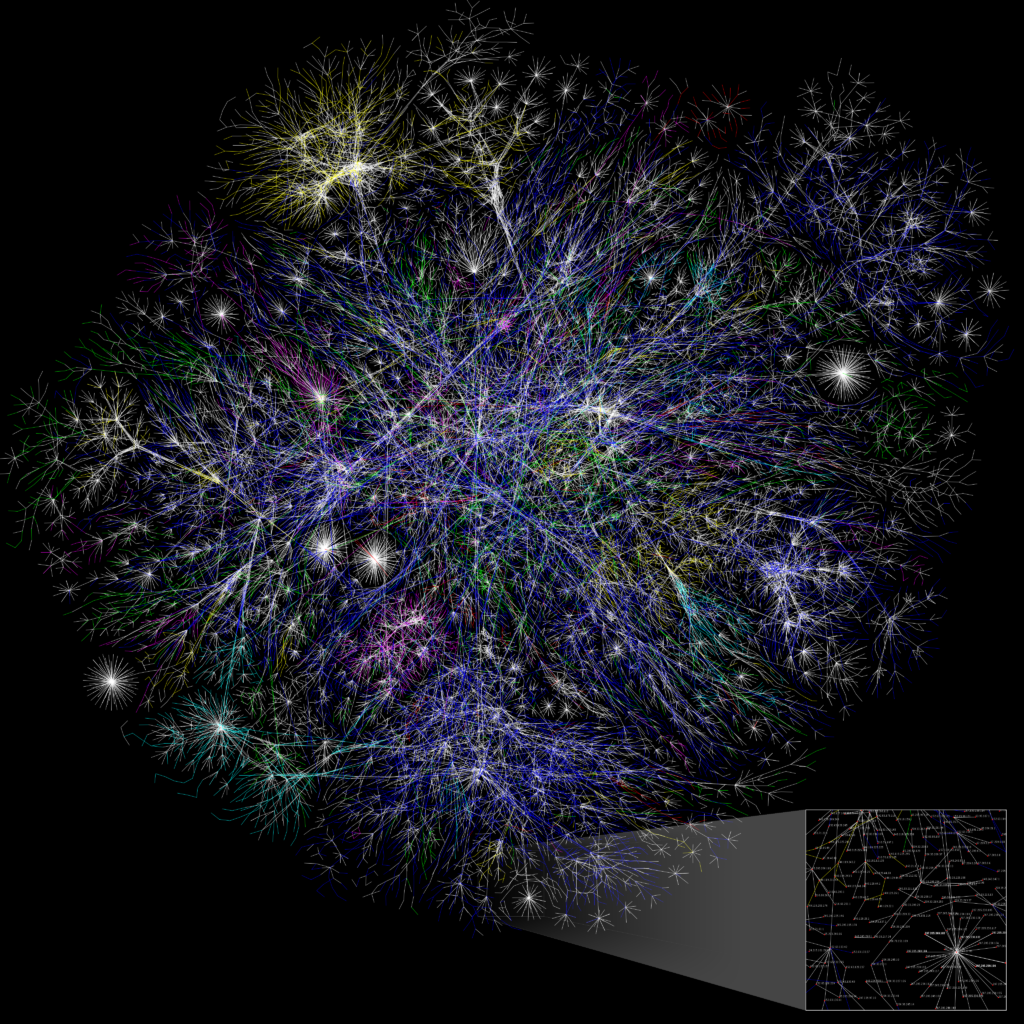

The anticipated quarrel with such a designation would be that much of what those voters received would not qualify as ‘recognized knowledge or scholarship; authoritative opinion; acknowledged expertise.’ But such a complaint misses the reality that by dint of appearing on the screen, information is perceived by many people to be ‘recognized knowledge, authoritative opinion; acknowledged expertise.’ We can freak out at the notion that the authority that matters most to our democracy now resides in an increasingly amoral and fact-optional ether, but we are troubling deaf heaven (and cloud computing) with our bootless cries. The internet, a bouillabaisse of Boolean bias and outright BS, is where 57% of U.S. adults often get news according to a 2024 Pew Research Center study . With that context, try on these figures, which, of course, I assure you, are accurate even though they came from the internet:

- In a Redline study, “about one-third (33%) of journalists encounter false or fabricated information regularly when working on stories, with 8% saying they deal with falsehoods extremely often and 24% fairly often.”

- Studies generally suggest that, year after year, less than 60 percent of web traffic is human; some years, according to some researchers, a healthy majority of it is bot. according to New York Magazine

- A Pew Research Center study conducted just after the 2016 election found 64% of adults believe fake news stories cause a great deal of confusion and 23% said they had shared fabricated political stories themselves – sometimes by mistake and sometimes intentionally.

- MIT scholars found that false news spreads more rapidly on the social network Twitter than real news does — and by a substantial margin. (And that was before Elon bought it!)

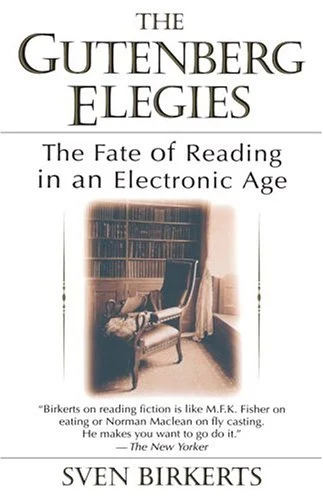

The situation fulfills prophecies of personalities as diverse as Terry Pratchett, the satirist and sci-fi novelist, Carl Sagan, the pop astrophysicist, and Sven Birkerts, the esteemed essayist as noted by Ed Simon in his essay on the latter’s prescience in The Gutenberg Elegies, a book published thirty years ago.

Simon now and Birkerts back then argued that the ‘electronic deluge‘ imposed upon those of us who willingly or unwillingly got wet produced ‘a changed understanding of reality.’ Birkerts predicted that “We would be swimming in impulses and data–the microchip will make us offers that will be very hard to refuse.” Thrust into “a kind of virtual now“, the reflection and deliberation that depends upon clear understanding of the past and disciplined analysis of the possibilities and perils of the future will become steadily more difficult.

But is this entity as pernicious as it can be actually a locus of authority for us?

Consider this comparison of authority versus persuasion as articulated by Dennis Wrong:

“If the essence of persuasion is the presentation of arguments, the essence of authority is the issuance of commands. At least in the short-run, coercive authority is undoubtedly the most effective form of power in extensiveness, comprehensiveness and intensity: … The counterpart of coercive authority is authority based on inducement, or the offering of rewards for compliance with a command rather than threatening deprivations. Legitimate authority is a power relation in which the power holder possesses an acknowledged right to command and the power subject an acknowledged obligation to obey.”

Did those voters feel that they were receiving a command to vote for Trump? Or even just to see the world in a specific way that would then dispose them to reject Harris? That may be true of the true believer variety, but that constitutes a smaller slice of the overall vote for Trump & Vance and they likely did not need any further encouragement.

Dennis Wrong offers another possibility, “In a relationship of personal authority the subject obeys out of a desire to please or serve another person solely because of the latter’s personal qualities.” Again, that seems to explain only those who had already surrendered to the ‘personal authority’ of Trump or who had close relationships with the die hard MAGA crowd. And most couples in a University of Michigan study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology “study shared similar political beliefs, whether it was their party preference or overall political ideology” so there isn’t a need to convert a partner via exposure to internet news and opinion.

So is the Internet Innocent?

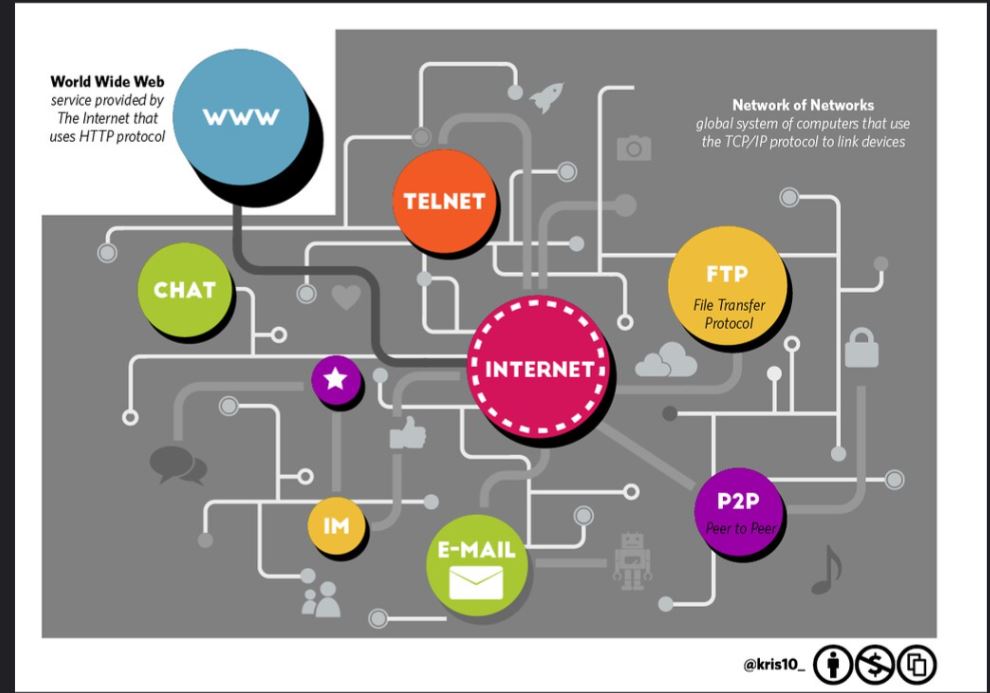

The way in which the internet (which includes the world wide web) might have persuaded the larger and decisive bloc of voters remains unclear. We know that the internet creates certain environments such as an echo chamber “a setting that reinforces rather than challenges existing beliefs“, but we don’t know whether or how that exposure to such an environment affected a vote — if at all. Studies such as research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2021 show that social media’s content curation creates political echo chambers, but that suggests its effect at most would be reinforcing rather than initiating or altering a decision to vote for a candidate. In fact, Pew Research Center findings suggest that the internet was a less potent force in the last decade:

- The number of people who found political discussions via social media “interesting and informative” decreased from 35% in 2016 to 26% in 2020.

- About 55% of social media users in the U.S. felt “worn out” by the number of political posts on social media, up nearly 16% since the 2016 presidential election.

- Nearly 70% of individuals said that talking about politics on social media with people on the opposite side was often “stressful and frustrating,” compared with 56% in 2016.

Accusing the Internet May Say More About Us Than It

Musa al-Gharbi in examining ‘bad election narratives’ criticizes ‘Most scholars and journalists (that) whenever analysts want to explain something they view as “bad,” they tend to focus exclusively on the red line people [Republican strongholds] – and they explain those “bad” outcomes in terms of deficits (ignorance, lack of cognitive sophistication, lack of empathy) or pathologies (racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, authoritarianism) among “those people.”

That explains why ‘The Internet’ is such an obvious suspect, but no one can tell us two things: 1) why doesn’t this authority work the other way? The Democrats spent 1.5 billion dollars and a lot of that was on social media. (I know as my feeds were stuffed with those messages.) 2) Exactly how does the misinformation or outright propaganda affect or swing the voting choice to go for Trump or to stay home? As al-Gharbi found in looking at the results, “Democrats lost in 2024 because Harris performed extremely poorly with women. Going all the way back to 1996 (when the partisan gender divide kicked into high gear), there has been only one Democrat who performed worse with women than Kamala did: John Kerry in 2004.” What message could the internet have supplied that served as the authority to shift previous voting patterns?

There are counterarguments such as the ones in this piece quoting Regina Lawrence and Seth Lewis: “Social media allows candidates to micro-target to reach very specific demographics of potential voters as opposed to television. It has also enabled politics to feel much more personal.” Yet that still fails to identify the mechanism of authority; we still don’t know the process of influence. And that will be our sleuthing focus next time.

My purely unscientific observation is that for many many people the decision was based on emotion, not the information being given. They were unhappy about how things are: prices, social pronouncements that didn’t make sense or alienated them, our position in the world, extreme wokeism and environmentalism, nannyism, etc., etc.. Something felt very wrong and that no one was acknowledging it to even saying they understood and would try to fix. Will Trump bring down prices? Calm down world tensions? Stop inflation? Make people more respective of each other without social mandates? Who the hell knows. Most likely not. BUT he talks about these things as if he “gets your pain” — you the anverage Joe, not the coastal Uber Luiberal, and acts like he wants to do something about it. Will he actually? Your guess is as good as mine.

I agree and my intention in this series is to get at that conclusion with some more depth and breadth; the mystery is how the decisions take place.