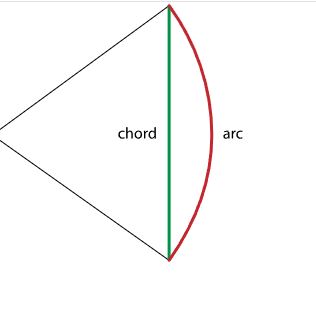

Chord: A straight line that connects the two ends of an arc

Many playwrights interested in self producing do not have the resources to avoid also holding down what people in the theater refer to as ‘straight job’. The phrase betrays a mindset that we also encounter; our theater work deviates from the straight and narrow, an ancient but still heard phrase indicating what the community deems as “the honest and moral or law-abiding way of life or … the correct and acceptable way of doing something.” Working in theater around the time that the phrase straight and narrow first appears — 1546, and very much in a religious context — was definitely not seen as a straight job. The Elizabethan era ‘Acte for the punishment of Vacabondes’ declared actors “vagabonds and masterless men and hence were subject to arrest and imprisonment.”) Today, the connotations of work as a playwright, actor, or producer lack that level of unsavoriness, but a straight job is still seen as something different: 9 to 5, regular, paying, maybe even benefits. It’s what many have to do in order to then squeeze into what hours and minutes remain their heartfelt desire of making theater live, to ascend the arc of a creative career.

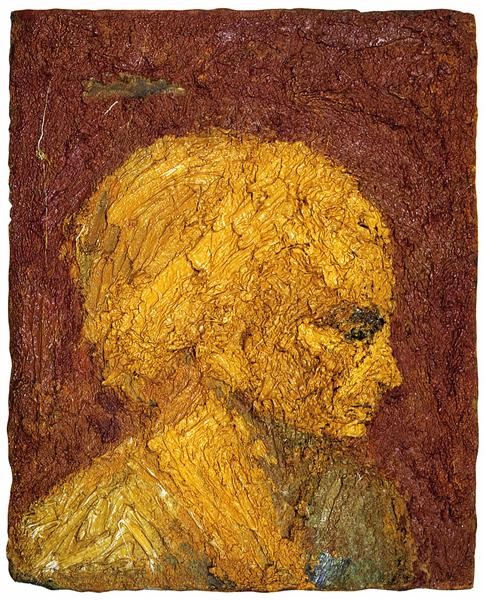

Straight jobs are not just a reality for those in the theater. Recently, the New York Times published an inspiring obituary of Frank Auerbach, the great British painter that carried passages that many a theater person would recognize and admire.

Frank Auerbach, a Celebrated and Tireless Painter, Dies at 93 This paragraph moved me especially:

Unable to earn a living solely through his paintings until the late 1960s, he taught, worked at a frame maker, took a job at the Kossoff family bakery in East London and at one point sold ice cream on Wimbledon Common.

Auerbach’s patience and ingenuity marks the self-producing artist. He believed not only in his ability to create something worthwhile but the necessity of his doing so even though initial circumstances didn’t favor such a pursuit. Isn’t that the case with so many creators who persisted until that effort changed the circumstances? Persistence is critical to achieving your goals. Patience must be an essential ingredient of persistence, perhaps even its ‘fundamental nature or essence’.

That’s not just my opinion. One of the great advantages of my straight job from almost twenty years arose from close association with scientists studying those attributes that make us successful. Two of them, Ralf Schulze and Rich Roberts, demonstrated that conscientiousness was a more important factor in attaining success than even intelligence. Looking at the psychological definition of that quality, several of the facets of conscientiousness required to find and do that straight job while also maintaining your creative efforts are in play: Industriousness, Procrastination Refrainment, Task Planning, and Perseverance.

This valuable trait in self-producers can be a double edged sword. John Dos Passos splendidly describes one difficulty that arises from applying ourselves to the straight job: that career encompasses us. Unlike characters in the TV show Severance, we do not shut off the other parts of our minds and spirits when we walk into the office or restaurant. We come possessing conscientiousness and, of course, creativity.

That latter quality, which includes the propensity to see connections, open-mindedness and centeredness, imagination, invention, and originality, also will surface in those workplaces often leading to requests to do more there for greater rewards. The stages of life are not inevitable, but they often involve increased expenses as we willingly take on responsibilities of partnership, marriage, and parenthood. Those needs tip our time/space scale toward the activity that is going to solve the problem of finding a bigger place to live or a better means of transport or making sure the kids are well-fed. That’s likely to be the straight job and since our resources especially our time remain finite such a calculation may reduce the amount of time available to make our art. If we add to the required hours to write a play, the additional blocks of time to

self-produce the resulting work the squeeze becomes evident, even palpable. The situation tests us. The good news is that like Frank Auerbach we can prep for and pass that test.

Yes, I think of the experience of holding a straight job and also working to self-produce a play as a test. Given my own straight job at Educational Testing Service (ETS) that I should propose this as one way of looking at life — and before people freak out I am stating plainly that it is only ONE way of looking at life — should not surprise anyone. Much to the consternation of even members of my family, I have long held that a viable and useful way of viewing our existence is as either a series of tests or just one long test. Obviously, I don’t consider a test to be inherently a bad thing.

Consider this definition of a test: “a procedure intended to establish the quality, performance, or reliability of something, especially before it is taken into widespread use.”

We are testing ourselves all the time as to whether we can do something, whether it is going to work out, whether its output is sustainable. That’s what Frank Auerbach did. He was testing his ability to keep up what mattered to him most, his daily painting, despite circumstances that might have thwarted another artist. Obviously, he passed with flying colors as they say. Requiem in pace, Frank.

Certainly, many people find tests of any kind stressful. Stress results when the perceived demands of a situation exceed our perception of our abilities. The stress of bending the arc of creativity to meet the straight line of the job that pays the rent can be of all varieties acute, event-based, daily, and chronic. The following very apt description by Peter James from his insightful blog Diary of a Failed Comedian fits what many creators (definitely playwrights and actors) decry, but undertake anyway because they believe (perhaps realistically) that their goals require this regimen.

“I’m glad I no longer have to be out at all hours of the night, riding the subway to different shows and open mics, attempting to grow and network my way into a functional career. I’m glad to be rid of the constant nagging sense of disappointment that comes with falling short of your goals. I’m glad I no longer have to shamelessly promote myself on social media, dying a little inside every time I press the “Share” button.”

Peter James makes a change

When fatigue and disillusion take hold, creators have several choices including abandoning such pursuits all together, pausing to recharge their batteries, and/or shifting their goals to another type of creativity that has less soul killing side effects. Good for Peter James for choosing the latter and subsequently giving us his takes on that world in essay form. That reality is why this guide to the self producing experience in theater emphasizes the cost — not just financial — of such an endeavor.

The warp meets the woof

“None Can say here Nature ends, and Art begins But mixt like th’ Elements, and borne like twins, So interweav’d, so like, so much the same.”

J. Denham

Playwrighting bears similarities to the ancient art of weaving. The woof are “the threads that cross from side to side of a web, at right angles to the warp.” Walter Benjamin noted the similarity: “Work on a good piece of writing proceeds on three levels: a musical one, where it is composed; an architectural one, where it is constructed; and finally, a textile one, where it is woven.” The architectural dimension of building a play was noted by Richard Schechner who wrote that we should think of “The playwright as wright — the play being wrought from the interrelationships among all the artists.” For me with a maternal grandfather who was listed on his Irish army pension papers as a cartwright, a carpenter who makes carts. My other grandfather was a mechanic who ended up running the NYC Sanitation Department’s 125th Street garage fixing garbage trucks and snowplows. This also suggests a parallel to playwrighting and self-producing.

In none of these pursuits can we focus only on the parts or the elements. We must admit to their interconnectedness., how they fit and influence each other The whole of self-producing life is not only greater than the sum of its parts, but insistent that we attend to it as a unity. All of the aspects of self-producing interweave. Breaking the experience into 13 Ways for this book is both useful and artificial. Dealing with the situation of the straight job is an example of how the totality of the experience, which as noted can be overwhelming, sends us back to employing several of the 13 Ways; self-reflection, self-care, self-esteem — yes, lots of self in self-producing. And it’s not for everyone every time. We may move in and out of that mode depending upon our circumstances.

The good news arising from our exploration of self-producing playwrights is that with the application of that critical conscientiousness they make theater. The straight job sustains and supports their creative arc. It is possible to make theater live while also making a living in other ways. What might be impossible just trying to understand everything that is going on while you are self producing. That act (like the act of its preliminary actually writing something worth producing) evokes the description of James Salter “You never know what you’re really doing. Like a spider, you are in the middle of your own web.” That means we must keep spinning and see what emerges.