A Brief History of ETS’s Recognizing Performance System

T.J. Elliott

June 2014

[Note: I wrote this account eleven years ago while still Chief Learning Officer at ETS, but having transferred the HR responsibilities to George Miller the year prior after holding them and other accountabilities organizationally since 2002. I would assume the HR portfolio again in a transition period in 2016-2017 and then shift to Knowledge Broker for the R&D Division of ETS under its SVP Ida Lawrence until my retirement January 30th 2020 when i returned full-time to running Knowledge Workings theater and writing — mostly plays. Reading this document now, I retain doubts about the way most organizations conduct performance management — the phrase itself is problematic for me as performance in my experience is more mysterious in its evolution and unfurling than management can fully encompass. But if an organization wants to have useful productive conversations about performance then this system co-designed by the late Janet Gillease and me still seems a worthy choice.]

An Unexpected Assignment

It has been over 12 years since then CEO Kurt Landgraf decided to revamp the performance management system at ETS. He had been CEO for over a year and had communicated his desire to Yvette Donado, then the new Vice President of HR (then called Strategic Workforce Solutions or SWS), to institute an ‘I-beam’ model of performance management similar to that described by GE CEO Jack Welch. Kurt had come back to ETS in 2000 after over three decades in the for-profit world where he had served in many leadership roles including CEO of DuPont Pharma and COO of DuPont Worldwide.

Why did he choose performance management for complete revision over other organizational systems? As he explained it to me in the spring of 2002, he had concluded that ETS was not managed properly, and that this deficit began with the management of performance. His main concern was that ETS leaders had become complacent even in the face of dire financial problems, which was the situation when he assumed its top job. His objective was to force managers to look more rigorously at the performances of their employees, and then to be required to take action when those performances were insufficient. He knew from his first days at ETS that many people not only wished to avoid discussion of performance, they failed to see a connection between performance of employees or units and the financial performance of the organization.

This cognitive dissonance persisted despite a condition that the CFO at that time Frank Gatti had described as “hemorrhaging cash” was perhaps not so surprising. The company was over half a century old, and had weathered other crises. ETS was the ‘Elephant’s Graveyard’ of change initiatives: TQM, Juran, Deming, Team Effectiveness were all fads that had risen and set on the campus. ETSers understandably thought that any new initiative would also come and go without making a substantial difference or requiring enduring change in the behaviors of staff. In fairness, ETS was still the most successful educational measurement organization in the world; its experts were the creators of the field and the guardians of its standards. What has shifted around these verities was the entry of competitors into ETS’s markets, the defection or disaffection of large customers, and the swelling of ETS’s cost structure. The filed moved from a ‘cost-plus’ mode to competitive bidding almost overnight. Even at that early stage of his tenure, Kurt believed the circumstances were critical: he spoke of a shift in performance management as a significant cultural change, which he acknowledged made it a more complicated initiative. That belief may have played a part in the accountability for the project residing with the newly created CLO position, which I had just assumed as my role.

My first notice that this project would be part of my job came as a surprise. I had worked at ETS as a consultant since July 2001. My projects were varied: development of an action learning leadership development program, review of compensation plans, consultation on change management as it was being conducted by yet another consulting group, etc. In November 2001, I conducted a search conference on the ‘Desired Future of Learning’ at ETS. As my colleague Willa Thomas (who was my primary contact at ETS during this consultant period and remains a valued team member today) put it, the leadership prior to Kurt Landgraf had decided that learning was unimportant. They disbanded the Learning & Development department and threatened to shut down as well the Center for Education in Assessment (founded by another longtime ETSer and current colleague Felicia DeVincenzi) responsible for making sure that assessment developers and statisticians have the knowledge necessary to do their jobs. Landgraf himself many times noted that the previous leadership had “disinvested in learning and knowledge management”, which he found very curious for an organization with the word ‘educational’ in its title.

At that search conference, 60 participants from throughout ETS decided upon a course of action to reach that desired future. Prominent among these actions was the selection of someone to coordinate all learning and development activities at ETS; e.g., a Chief Learning Officer or CLO. (Performance management did not appear on the list.) I had dinner with Yvette Donado at the end of the search conference and mentioned to her my interest in the CLO position if ETS was going to recruit for it. I was hired in January 2002 after interviewing with Paul Ramsey, then Senior Vice President at ETS. I communicated my acceptance of the position only to be promptly (and mischievously, I think) informed by Yvette that the first priority for me was to design and implement a new performance management system for ETS.

I didn’t associate that job with the role of the CLO, and I think at that time there were relatively few Chief Learning Officers who also had responsibility for performance management. In subsequent years, I’ve come to understand that Yvette bestowed upon me a powerful gift in assigning this design and implementation to my office. Performance should be about learning and performance management or review should have at its center conversations that allow all parties to interpret the world more effectively and efficiently. Therefore, if I had to do it all over again I would emphasize even earlier and even more the learning aspect of our Recognizing Performance system. That was something I learned from the experience.

Designing Recognizing Performance

At that time, however, I was concerned that there were already significant political forces associated with the idea of performance management at ETS. Landgraf as CEO had made a videotape with the previous Acting Vice President of HR in which he outlined his plans for an I-beam type system. Other officers had their own notions of what a system should look like ranging from new criterion based systems to maintenance of the existing hodgepodge of divisional distinct practices to Cost of Living Adjustments schemes. While these officers mostly were careful to shield their opinions from the CEO, they did advocate for them among their fellow officers.

Yvette knew that I had had experience setting up performance management systems for other corporations including her previous employer, Donovan Data Systems. None of them were I-beams, but all of them emerged from a careful design process that avoided any presumptions. Many of them had a requirement of increased differentiation of rewards. Design is a matter of responding not only to the requirements of your customer but also to the realities of the environment and the lessons of past experiences. I knew from my previous work in this arena that the harsh rigor required for an I-beam was a tremendous challenge for managers. My opinion of ETS based upon my several months of consulting there was that the culture in that organization was unsuitable. It would prove too much of a shock to a culture that was in part academic. An I-beam may have worked at GE, but ETS was as Landgraf himself liked to say “a research university stapled onto an L.L. Bean.” I also knew that the I-beam was known through articles in the popular press and disliked by the general public more than any other performance management system. Insisting upon an I-beam approach would misfocus our efforts and the attention of all ETSers as we tried to create. Instead, I focused on the interests Kurt held as he entered his second year of ETS’s ‘turnaround project’. I started to look at a system that would differentiate performance fairly and transparently and provide rewards based upon that differentiation.

In this work, I had a co-designer, Janet Gillease. She wrote me on April 18 — just two months after I started at ETS — that she “wanted to re-iterate my interest in working on the Performance Mgmt. System project. No, I’m not a masochist! I like challenges, get energized about the topic, really can ‘play within bounds’ and feel that I can really make a contribution. (I’m willing to put in long hours etc.)” One of the things was very attractive about having Janet as a partner in this unusual project was that she was coming to ETS from a career at Mobil E&P, where during the 1990s, she was a “key contributor to implementing several iterations of performance management systems. systems (some traditional, some more innovative) under similar pressures.”

We met and tried to divine how to fulfill the key interests of Kurt in a system that would look very different from what ETSers had experienced previously. The CEO’s dominance of the Business Council meant that if we satisfied his requirements our plan was likely to be approved by the rest of the leadership. We reviewed transcripts of meetings that he had held, videos of him speaking about performance, and notes from my boss Yvette Donado on her conversations with him. We determined that his primary concern was fairness. Whatever system we devised had to be fair to all employees.

We discovered only later why this quality was preeminent in his and others’ minds. As we prepared for and then undertook the first Recognizing Performance implementation, we discovered material that suggested to us fairness was not present in previous incarnations of performance management at ETS. One of the ways in which inequity manifested itself was that senior managers tended to give greater increases to those higher up in the salary structure, which in that zero-sum game meant that those at entry-level positions, clerical jobs, call center positions, and other less exalted jobs tended to get raises within a very narrow and low range. This related to what we believed to be Kurt’s secondary requirement: differentiation. We translated this into the principle that “Managers make investment decisions “in a performance management system. This necessitated the system being norm- rather than criterion-referenced. In other words, results would be judged against other performances in a relevant job family rather than against some abstract standard. This emphasis upon a result rather than an attribute was a major difference, but it fit with the notion of such decisions as investment decisions. If managers in determining the merit increases that would affect employees next year, we were going to use distribution guidelines as a framework to significantly reward people who have produced the most important results than an element of competition to be present in Recognizing Performance.

Photo by Denise Krebs mrsdkrebs

We were careful not to claim equality as one of the characteristics of this system. There is a significant difference between equality and fairness; the former guarantees much more. Fairness promises freedom from irregularities; equality promises freedom from significant differences. Additionally, by focusing on job families, we sought to make comparisons among results that belonged to people in similar roles; a program manager and a software coder could not be compared sensibly. As I wrote to Les Francis, then our Vice President for Communications, it would be inaccurate to say that “performance decisions will be equitable throughout the company. … Equity throughout the organization is not an outcome of our system. Decisions will be equitable throughout a division, but each division has different Criteria for Performance Review. Therefore, the process of differentiation is the same throughout ETS, but the criteria for what makes a performance relatively important varies from division to division. Small point, but the statement (of the system being universally equitable at ETS) would be seized upon by test developers and researchers as a false claim for the system. “

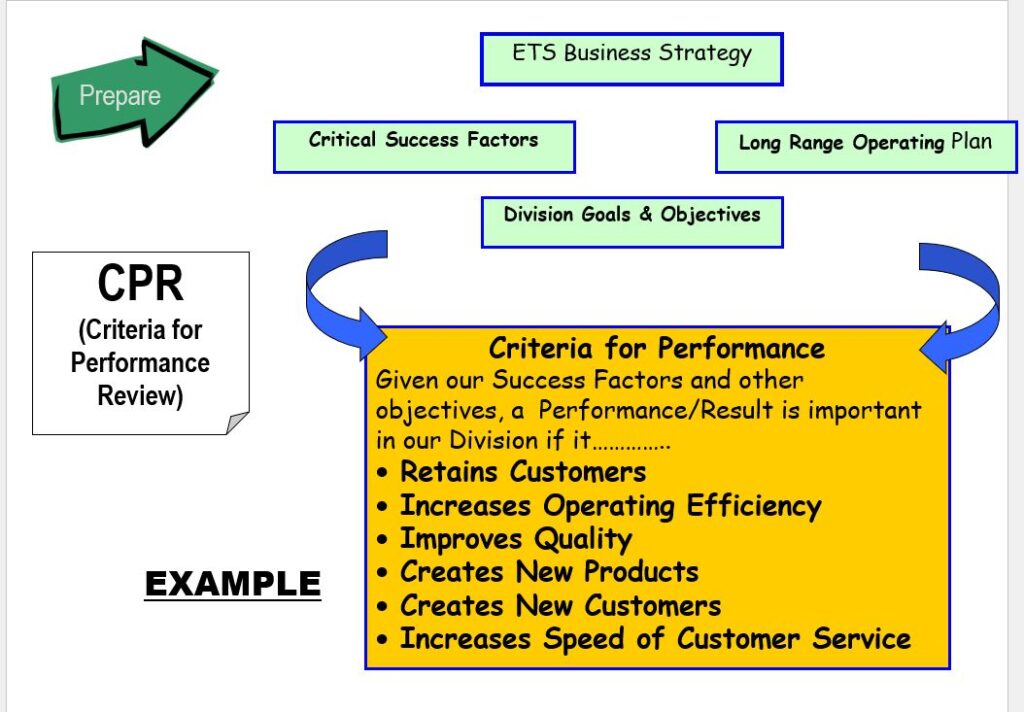

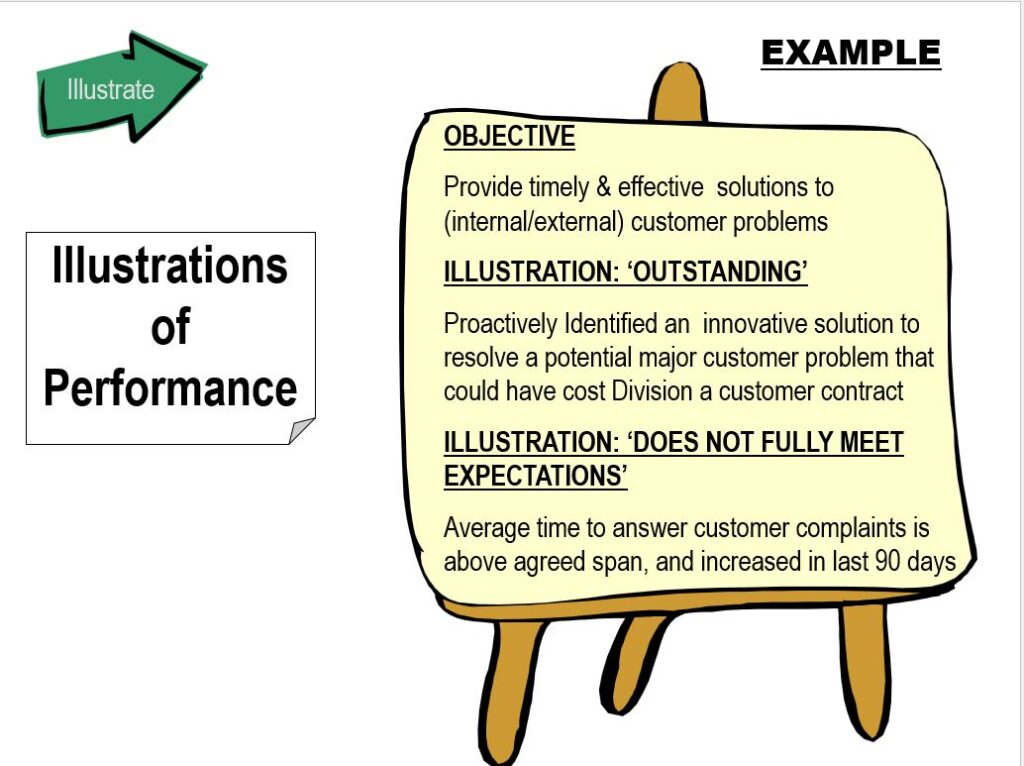

Those Criteria for Performance Review were an outcome of another of Kurt’s requirements that we divined: transparency. Everyone had to have the ability to see how decisions were made. This also let us to employ different decision-making techniques than had been used previously. Instead of individual managers making these choices about where an employee was in the overall group, we created job families — collections of similar roles. The decisions about those roles would be made by all of the relevant managers with facilitation from HR. The vice president for each division would stipulate these criteria by which performance should be reviewed. It was a simple formula, “a performance should be deemed as extraordinary if it…” Some vice presidents chose financial measures. Others proposed more abstract statements such as “advances the ETS mission.” For the first time according to any documentation we consulted then or have discovered in the ensuing dozen years, ETSers had access to more specific information as to how their performances were going to be judged. We shared not only these criteria but the guidelines for the entire process.

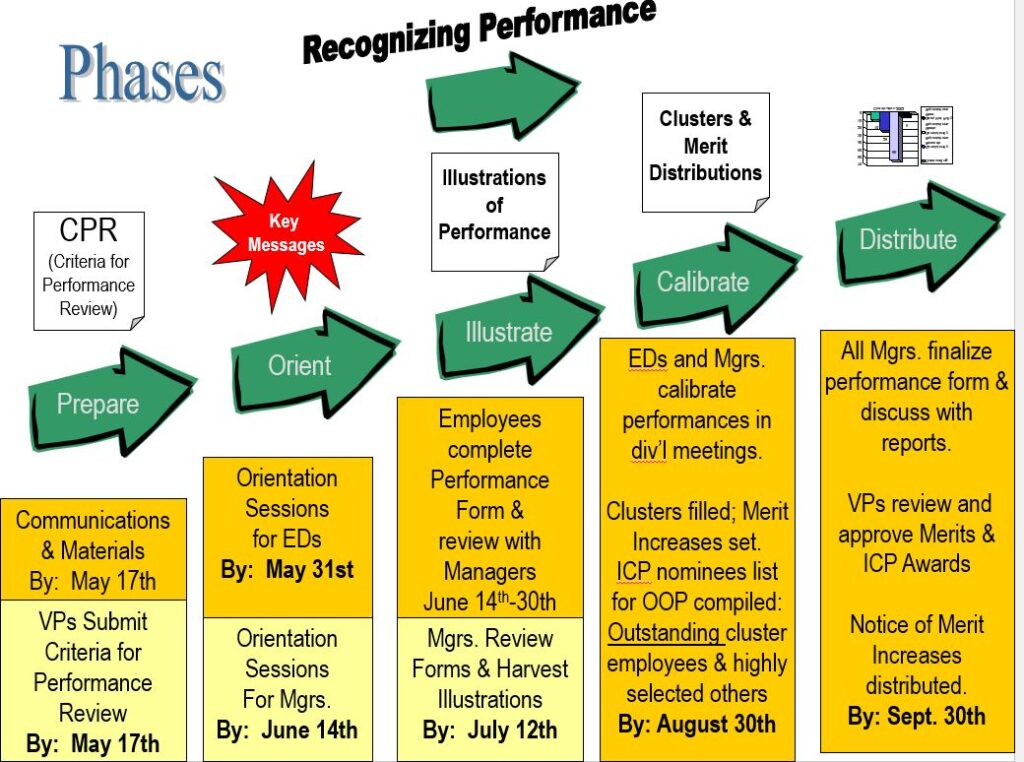

These principles guided the design of a calibration process. After vice presidents set Criteria for Performance Review, managers in a particular job family would suggest illustrations of performance at the highest and lowest levels, and then as a group, those managers would ‘harvest’ illustrations for comparison and conversation. That discussion would lead to the placement of each individual employee in a cluster. Kurt dictated to us the percentages of employees that should fall into each cluster and the accompanying range of merit increases for which they should be eligible. We negotiated different numbers from his original suggestion that included a demand that fully 20% of the employees receive little or no increase.

Realities and Resistance

Devising that process once Kurt had agreed to these requirements proved much more difficult than we imagined. One of my major mistakes was not exploring the existing patchwork of systems more thoroughly to determine the current status. Thus we kept on discovering missing elements as we designed the new system; e.g., arriving at 7 AM one morning, I encountered a frustrated Janet who informed me that there was no electronic system in which previous performance reviews resided. It was too late to create one in this first year of Recognizing Performance. Therefore, our design had to employ a cumbersome and logistically challenging system combining paper and PowerPoints. That meant coordinating physical files for 2500 employees in addition to all of the preparatory work necessary as ETS also lacked a learning management system. A check of employee files found that many even lacked a paper copy of some of their most recent ‘reviews’.

The far greater challenge for us lay in the scope of the change. We were asking all of the employees (and especially all of the managers) to think differently not only of how they did reviews, but of how they viewed performance. Many divisions enforced a kind of equity in which no one was allowed in a particular job class to receive rewards that were much greater than his or her colleagues. Some newer arrival in the leadership corps carped that there was a sort of socialist ethos present in much of ETS. This characterization was extreme. Concerns about differentiation were rooted in part in the academic nature of the work. They also could be traced to the work experience of much of the population. Many ETSers had never worked in a for-profit institution. Introducing the concepts of comparison and differentiation embodied in Recognizing Performance was a shock to their individual and tribal systems.

A review of the emails from that time (which I archived along with all of the materials that we created and used) demonstrates that we spent most of our time explaining, persuading, and shepherding those who were going to lead the process: managers. (This also seemed to be a difference; VPs previously may have dictated the decisions in some divisions.) Our colleague, Susan David, undertook a great deal of the training associated with the new system; she had been at ETS as an L&D staffer. She devised and ran classes on Managing Successful Performance Conversations. These interactive sessions contained exercises to generate ideas among participants about what makes such conversations successful — from the feedback giver’s perspective and the receiver’s perspective. Our goal was to change the mindset while also changing the process. Publicly and privately, many observers expressed doubt if not outright skepticism that we would succeed in implementing Recognizing Performance. And their handicapping was not misplaced; several senior leaders expressed not only their hesitation but also their resistance.

In fact because of the widespread resistance, we decided to bring in professional facilitators because we realized that the skills needed to navigate those currents of resistance as encountered in the actual calibration sessions were not present in our HR consultants. They simply lacked the experience for the most part. In one isolated case, one of them joined the opposition and publicly declared Recognizing Performance as impossible to implement.

The resistance, however, started at the top. In order to determine the final distribution scheme, Kurt directed me to meet with the Business Council without him present. He wanted to know what they would decide. They argued among themselves with a substantial faction trying to reduce and in some cases even eliminate any differentiation. One Vice President suggested we scrap the whole idea and simply provide a cost-of-living adjustment. Kurt came back into the room and informed his officers that their deliberations were unsuccessful. Agreement was quickly reached on a distribution matrix that allowed rewards from 0 to over 10%.

A related discussion was whether to actually use labels such as ‘Cluster 1’ to designate where employees landed in this differentiation. Kurt felt very strongly that the labeling was a bad idea. However, as we pointed out at the time, human beings like labels; they are easy signs of some reality — even if they belong to a process they abhor. Recognizing Performance not only has had to deal with this issue of labeling throughout its existence, but eventually in practice managers, HR (later SWS) consultants, General Counsel Office employment lawyers, and many other players routinely used the label in conversations and decisions about employees. More on this effect when we discuss Unintended Consequences

Early Implementation: A Critical Distinction

The interactive nature of the communication campaign extended to informational sessions that I conducted as the co-architect of the new system. Reactions ranged from uncomfortable silence to skeptical questioning. However, at a standing room only session of assessment developers, a critical shift occurred. In explaining the way in which the managers for a particular job family with calibrate the results of each individual against the Criteria for Performance Review using as anchors the illustrations harvested prior to the meetings, Steve Lazer and Walt MacDonald, then Executive Directors in that area, made important comments that not only calmed the crowd there, but also provided a context for what we were doing that was both understandable and justifiable to the employees of the world’s leading educational measurement company. First, Steve and then Walt pointed out that the underlying scheme of the calibration sessions was similar to the scoring regimen for Advanced Placement essays. The illustrations provided the ‘rubric’ and the managers constituted a group of raters. It was Steve who pointed out to those assembled that Recognizing Performance was a norm-referenced exercise, which if executed properly would resemble what ETS itself did for certain classes of test takers. Shifting the understanding of performance management to being a process that allowed us to make a ‘claim’ about an individual based upon his or her results and not some attributes furnished an important rationale for the program. Steve and Walt in a few seconds provided the words that would allow us to explain what was going to happen, how it would unfold, and why the primary requirement of fairness was met in these procedures. Without their intervention that day, I doubt that the implementation of the system would have proceeded as successfully as it did.

Managers were not the only force of resistance encountered as we began the critical communication associated with the rollout. The skepticism and suspicion of average employees was powerful, but had an advantage in that it helped me learn some important lessons about change. Whenever those of us who are so-called ‘change agents’ in an organization unfurl that work, we espouse and advocate a particular future because of our values or those of the change’s sponsor. The people who must enact the change (or how are having it enacted upon them) also have values, and those attributes are trampled by the new way of doing things. As I learned from reading Don Tubesing, many years before Recognizing Performance came into view, when events collide with an individual’s or team’s belief system stress results.

All of us establish early in our lives what the psychologist Don Tubesing termed “belief systems,” ways we expect the world to be, and the way we see ourselves within that world. Our belief systems may come from many sources, such as family, schools, and peers. They include our values, what we think deserves attention, our self-concept, and our motto or abiding slogan by which we parse life. Now in making and receiving these decisions on performance as a result of the new process we were injecting stress into the lives of all involved. Good intention? yes. But we had to deal with this effect in the midst of the decision-making required for Recognizing Performance to accomplish its goals. We were creating conditions that challenged the exiting values of many at the company. And values matter enormously in decision-making.

Moscovici and Doise write convincingly of the power of values upon decision-making:

“Each individual comes to the task with a capital of knowledge and methods on which he can draw in fresh discussions and negotiations with others. In this capital, values in particular are included, some of which we have acquired, but the majority of which have been inculcated in us almost without being aware of it. They have been imbibed, as the saying goes, with our mother’s milk. That is why individuals, like groups, choose with the help of what they have not chosen. These values … are like moulds in which is shaped the mental space in which decisions take place, just as physical space is shaped by vectors.”[i]

The values that guide the individual in various roles as decision maker are:

- Happiness

- Lawfulness

- Harmony

- Survival

- Integrity

- Loyalty

Think of what a new performance management impacts when it is a new regimen that required people to rank their colleagues in terms of relative output, that involved conversations in which all must articulate their own methods of working, and that made these decisions more consequential

When these ways of seeing the world, these beliefs about what “should be” are challenged, great stress results. So the first impulse is to stay inside our frameworks, but we could not let that status obtain.

Everything that we were doing in RP was different for those involved: conversations, forms, meetings mindsets. We were as the saying goes ‘carriers’ of stress. We had to understand the interests of people if we’re going to be successful. Those interests were very varied: some just wanted to avoid the hassle of learning new things; others were terrified of having the group manager conversation. This would require a whole different way of communicating with their peers and reports. Still others felt that the system would block their receiving the maximum reward available. In listening and clarifying, we were not addressing all of these concerns, but we were acknowledging the tradeoff between what ETS would get in fairness and differentiation. We started more and more to empathize with and even emphasize what people were losing in the new system rather than simply trumpeting what was to be gained. However, we had to do so in such a way that acknowledge our limitations; we could not deviate from what we consider to be the ‘user requirements’. And for this system, the user was Kurt Landgraf.

Calibrations and Calculations: The First Run of Recognizing Performance

After a few years, the fiscal year of ETS changed and calibration sessions were conducted in the first quarter of the calendar year. But in that first year — 2002 — the sessions with managers crammed into rooms happened during a sweltering July and early August. And the rooms were papered heavily with the artifacts of this new system. I got to see more than once the curious stares of participants as they walked into the room only to discover that our teams had already posted on the walls dozens of illustrations of both positive and negative results.

We wanted illustrations of extreme results; those that had added extraordinary value and those that may have actually led to the subtraction of value or at least additional work and expense. We gave people examples; e.g. an employee whose job was to perform editorial reviews might have a result that showed that his contributions lack accuracy and often required costly rework. All of this took a great deal of time but more importantly required contortions to the usual mindsets of many managers. Who actually discussed performance in such detail? When were supervisors required to explain to other supervisors and, in some cases, strangers the conclusions they had reached about the performance level of one of their employees? Actually documenting illustrations of high and low performance as a prelude to discussing them caused significant anxiety. Being explicit about what we referred to as “investment decisions” — merit increases and Incentive Compensation Plan (ICP) nominees — produced significant discomfort. The idea of constructing and then applying a framework to significantly reward people who have produced the most important results disturbed a culture that favored spreading rewards as equally as possible. Talking first about results and only then about people proved impossible for some of those early managers; the employee and his or her results were entwined.

Janet and I thought that this feature of the program was very important. However, our aim failed to take into account sufficiently human nature. While technically it was possible to separate out results from the individuals who had produced them, realistically managers spent a great deal of energy in these inaugural calibration sessions endeavoring to identify who the person was who had produced the result. Although this awareness led to a number of biases, we were forced in subsequent years to acknowledge reality and simply let managers talk about results and people at the same time.

When managers actually got into the rooms, our decision making formula was explained — and again provoked consternation. However, this feature of Recognizing Performance was embraced by many of the managers. The fact that the supervisors had to review and reference the Criteria for Performance Review changed the conversations; individuals who had an eye to gaining advantage for their people came prepared with evidence to support their assertions. As one senior vice president pointed out to me, ETSers were not used to this kind of advocacy. However, those managers who had been involved in other companies or were more comfortable with debate had a significant advantage as they understood not only the value of evidence but also the necessity of argument.

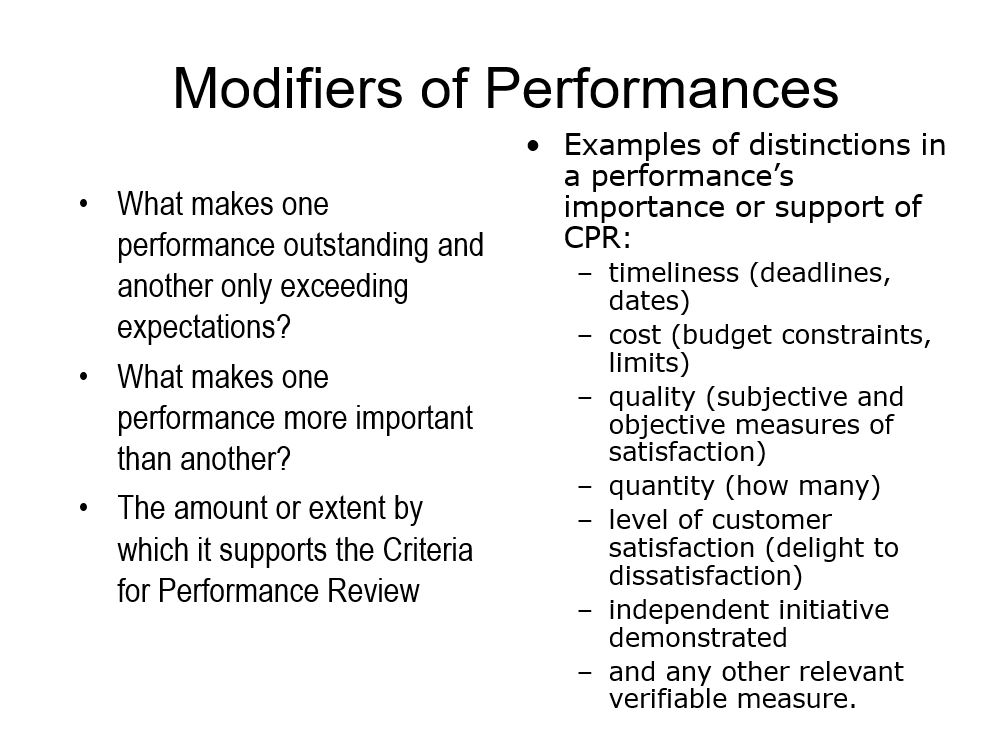

I’m sure that many ETSers would disagree with us, but Janet and I saw this is a good thing. We believe that those conversations about what constituted good, average, and mediocre performance needed to occur. We specifically phrased this activity as deciding, “What makes one performance more important than another?” Additionally, we supplied examples of distinctions and performances importance or support of the CPR:

- timeliness (deadlines, dates)

- cost (budget constraints, limits)

- quality (subjective & objective measures of satisfaction)

- quantity (the sheer volume of notable results)

- level of customer satisfaction (delight to dismay)

- independent initiative demonstrated (how much of a manager’s bandwidth did an individual require to get the result?)

While these were suggestions, we allowed that the conversation could use any other relevant verifiable measure. What we were most interested in was fairness, and we thought that putting as much information before the group as possible with guidelines and criteria to be agreed upon as to how the importance of the information would be determined created that sought after fairness.

One of the elements that we understood right away was the importance of not promoting this program as reaching the standards of validity and reliability that ETS manifested in its educational measurement. We recognize that this new system was making a claim. However, we were quick to explain the limits of that claim — both in our initial communication and throughout the calibration meetings. This proved to be important as in the meetings those with statistical backgrounds would start to talk about distribution curves or inter-rater reliability. Some friendly stat analysis folks helped us to determine the number of illustrations of highest results and lowest results that were required for a ‘good enough’ calibration; an amount equivalent to 40% of covered employees of the good variety, and 20% of covered employees of the negative sort. In order to get folks to generate the results, we pointed out that it was highly probable that employees without illustrations of top results represented in the calibration would not make it into the top two performance distribution clusters. In this way, we made clear that submitting illustrations results for any employees the manager believed belonged in the top clusters was imperative. (Employees in the highest cluster were automatically nominated for ICP awards, but managers could also nominate other exceptional employees.) Given Kurt’s ‘user requirements’ we also pointed out that it was critical that managers submit an adequate number of low illustrations in order to identify employees that were the lowest performers, even in relative terms.

As with many of the initiatives that we undertook in those early days of ETS cultural change, Kurt’s support was powerful. For example, within the calibration training sessions we made the point of needing to have a distribution by distributing Kurt’s endorsement (some would say ‘demand’) that the entire organization hit the marks established for a range of merit increases. However, CEO support and even coercion would not have produced the shift that we saw spreading as the calibration sessions occurred. Our communication both before and during the session emphasize that while the requirement was to see the range the application was up to the people in the room. They had to decide the range and where people are in that range. Our outside consultants brought useful perspectives that we wove into the communication; e.g., distinguishing between an appraisal and a system to make folks understand the advantages of the latter, emphasizing the opportunity to help people improve, reinforcing that the role of the manager was to make decisions. This last point seemed to resonate with many participants. I believe that the structure of ETS before Kurt Landgraf arrived circumscribed sharply the kinds of decisions that an individual manager could make. And decisions were rarely reached in a collaborative setting. Many managers enjoyed the fact that they were making decisions.

How many of those participating appreciated that shift in their responsibilities? The feedback received during the sessions, the information gathered in an after action review that deliberately invited critics of the system, and employee opinion survey comments from the next two administrations of that instrument indicated that the overwhelming majority of managers appreciated the shift. They understood that our primary purposes of sharpening our focus on business results, differentiating performance in a disciplined, meaningful way, and recognizing and rewarding significant contributions made sense. They acknowledged that there had to be a connection between merit increases and the achievement of ETS objectives to produce the yearly revenue to fund compensation pools. They respected the fairness and diligence with which the process was conducted. We made it clear that no labels were to carry over from previous years, that each employee had an opportunity to get fresh objectives and, therefore, the chance for different results and the concomitant merit increase each year. The transparency of making public the main documents and mechanisms along with the consistency of insisting upon adherence to a particular differentiation process across all divisions made people feel better about this activity.

One of the aspects of fairness was to allow appeals that would be heard by the vice president of what was then HR and what would become Strategic Workforce Solutions. In the first 10 years of Recognizing Performance, there were fewer than 10 appeals out of almost 30,000 appraisals. While there were employee opinion survey comments indicated that a small group of employees were dissatisfied with how merits were doled out, that percentage was lower than the percentage of actual employees who received below average merit increases.

Unintended Consequences

The intended consequences were achieved. ETS managers had evaluated every employee in a group setting and awarded merit increases according to the prescribed schedule of differentiation. Fairness, rigor, and transparency were present in all the proceedings. However, there were many consequences that were unforeseen and to a degree unsought. Having a record of performance based upon documented results changed the dynamic of many employee-manager interactions. Where discipline was contemplated, the manager now had to explain to the employee (and to HR) why there was incongruence between the action contemplated and the documentation in the system. We discovered that managers in some cases had provided illustrations of results that did not reflect the actual work employees in question.

As noted earlier, once we had put people into four clusters it was impossible to avoid that designation being a part of so many other processes such as discipline and development. This reality meant that we had to explain repeatedly in disciplinary meetings, succession planning sessions, and other conversations about people’s performance and their potential that extrapolating the meaning of a cluster designation beyond a particular job family in a particular year was wrong – and eminently unfair. However, again and again throughout the entire life of Recognizing Performance, managers and especially officers would interpret a cluster assignment globally that should only be understood locally. In other words, a partial failure of the implementation was the lack of comprehension by some managers that the comparison of results occurs against other results in the job family based upon a divisional set of Criteria for Performance Review. Therefore, that claim has no relevance when compared with another job family. Some of those units managed to have performers who were all excellent in both their skills and their application of those skills to produce results. Other units had more of the distribution. Still other units lacked anyone who demonstrated possession of the qualities necessary for consistent success.

In that first year and ever since when I come across someone who is misinterpreting a cluster designation, I compare what happens in a calibration session to a track meet. Each one of the job families might be thought of as a ‘heat’. Some of those groupings are filled with fast runners, but some of them might have been one or two superb performers. Finishing first in the latter type of heat could not be compared to being the ‘winner’ in the former instance. The first-place finishers in a high school section of the Penn Relays cannot be compared to the first-place finishers in the college division. However, they all ran the same distance. What makes it even more complicated is the comparisons among job families are like comparisons between the shot put and the hundred yard dash.

I cannot claim that we were completely successful in making this distinction. While we could insist upon it in certain deliberations, especially after I became responsible for HR processes in late 2004, senior leaders required correction again and again as they tried to extend inappropriately the meaning of a cluster placement, and this including Kurt. For example, a leader might speak of cluster threes as describing a meaningful class of performance, and we would have to point out — again — that each job family set its own definition of performance at each cluster. Comparisons among job families are and were inappropriate.

There were many other aspects of the program that we did not envision in that first implementation. What would happen if a poor performer had been fired just part of the calibrations? With the manager be penalized for having done a good job of moving out someone who was a poor fit for their job? Janet Gillease worked with the HR consultants to make sure everyone had the up to date information so that VP areas could still get “credit” in their distribution for any poor performers that were already let go during this performance period. Any poor performers already let go in that first year could be “added” back into the bottom cluster of the distribution and be counted towards meeting the 5-15% bottom cluster. “

Similarly we discovered that employees who had been out on short term disability or family medical leave were at a significant disadvantage under this system. While the rationale of paying for results in the distribution of merit increases was solid, disadvantaging someone in their year-over-year income opportunities because of events that were outside their control (and likely had already depleted their resources) ran against our commitment to fairness. Adjustments were made in this area as well.

Time for Something New

As the years went by and ETS’s corporate results improved significantly (you could look it up), the Recognizing Performance system changed. We achieved efficiencies that cut drastically the amount of time spent in calibration sessions without sacrificing the quality of discussions. However, since the circumstances that prompted the creation of this particular system no longer obtained, Janet Gillease and I as co-architects spoke many times of the need to reconsider its requirements. When Kurt Landgraf in 2012 announced his impending retirement, I spoke openly as Vice President of the HR function of the need for the new CEO to revisit performance management at ETS. I’m delighted that my successor in that function, George Miller, and two of his very able lieutenants, Dan Papa and Eric Waxman are leading the organization to such an outcome. Their work is helping us again to learn, to interpret the world more effectively. Performance management systems like every other artifact of an organization exist to serve the creation of value, not to be served by the employees and managers. As Thomas Jefferson once observed in a different context, having a revolution every once in a while is a very good thing. Questioning our assumptions and shaking up our beliefs is often part of realigning ourselves with how we will create value desired not only by us but also by those whom we ultimately serve and, in the case of ETS, for whom we ultimately exist. Whatever the successor to Recognizing Performance ends up being, that system needs to serve people worldwide by making sure that ETSers’ performances achieve ETS’s mission

Note from 2025

Just because I left corporate life 5 years ago doesn’t mean that I stopped thinking about certain concepts (learning, measurement, knowledge, decision-making, and especially performance) that enveloped me during my decades in that existence, what I like to call my ’straight job’ years as opposed to the ones in theater. One of the reasons for that continuation of pondering these elements is that they’re part of any endeavor not just formal organizational life. I once wrote In an introduction to Joe Raelin’s book on work-based action learning that performance is a promise fulfilled. We accepted the responsibility to do something and our performance is about making that happen.

But the reality is not as simple as that formula because there are many other factors involved in what turns out to be our performance. One of the great frustrations of my time especially at ETS but with all corporations where I worked or consulted was the failure of many in senior Management to realize that control over performance by the individual worker only amounted to about 30 to 40% of what would result. This finding was so counterintuitive to them because they wanted to believe that 100% of the result was directly attributable to the efforts of the individual. They discounted whether the person had the right tools. They disbelieved how much the person having the right manager made a difference. They dissembled about whether the task was the right one or rightly explained to the worker. They often dismissed whether in fact they might have made a mistake and put the wrong person in the job in the first place, which would have made any deficit in performance their responsibility.

I wasn’t making any of these things up. There’s a whole tradition of human performance technology with lots of research that points out the significant influence of these other factors. Thus, I have some regret that in being the co-architect of this performance management system (and the sole architect of similar ones in banks, colleges, and even Fox News — yes Fox News –before I got to ETS), that these nuances rarely received the attention they deserved. In the current state of the world, the opportunity to perfect or even just refine these kinds of systems so that everyone prospers seems to be diminished if not disappeared. But we shouldn’t stop trying. Intelligence and Humanity require us to do our best for each other in this regard.

[i] Moscovici, S. & Doise, W. (1994) Conflict And Consensus (W.D. Halls, Trans.), p. 47. New York: Sage.