You did it! The house opened, the seats filled, lights dimmed, and then rose again in the proper pattern to illuminate your story and the marvelous set constructed for this occasion. The actors costumed brilliantly moved and spoke as you imagined. Well, mostly as you imagined because the direction and their own imagination have brought new layers to the work. And now if you have done the job of publicity successfully, you’ll get to read some reviews. Don’t let them affect you too much.

(While the initial premise of this series — 13 Ways of Looking at Self-Producing — limited the observations about the experience of playwrights putting on their own work to thirteen perspectives, we only mentioned reviews glancingly in that sequence, and their rigors, realities, and ramifications deserve more attention. This post — a Bakers Dozen plus one — corrects that omission.)

Why do I offer that advice? Foundationally, I agree with the great poet and essayist Louise Gluck about what it takes to be a writer, which she described in a somewhat negative way explaining why her own father did not become a writer:

“…my father wanted to be a writer. But he lacked certain qualities: lacked the adamant need which makes it possible to endure every form of failure; the humiliation of being overlooked, the humiliation of being found moderately interesting, the unanswerable fear of doing work that, in the end, really isn’t more than moderately interesting, the discrepancy, which even the great writers live with (unless, possibly, they attain great age) between the dream and the evidence.”

Louise Gluck

In order to read the reviews usefully, you need those qualities even the best player in the best production is going to be viewed by someone out there with access to a website as a critic as having failed or only been found moderately interesting. It is highly likely that the ‘evidence’ of the review will be discrepant with whatever you and your team held as the ‘dream’.

DISCLAIMER: my relationship with feedback on plays resides in the eccentric column. I’m not looking for opinions about the work in the same way that many of my colleagues do. It just wouldn’t work for me. Jean Cocteau offers advice that makes sense to me: “Listen carefully to first criticisms made of your work. Note just what it is about your work that critics don’t like — then cultivate it. That’s the only part of your work that’s individual and worth keeping.” My process of writing and rewriting and then rewriting again depends almost exclusively upon my ‘familiars’: team members who have been with me from even before the eight productions of Knowledge Workings Theater, actors that I know trust, and a few other friends whose taste matters to me. So, the disclaimer is that I start off differently in my encounters with reviews than many other playwrights.

But there is a significant difference between getting feedback in forms like this one or NPS and getting a review. The wisdom of Edna St. Vincent Millay comes to mind “A person who publishes a book willfully appears before the populace with his pants down. If it is a good book nothing can hurt him. If it is a bad book nothing can help him.” And that’s just a book that might not even have your picture on the inside flap. In the case of the self-production of a play, the situation seems to be more full frontal nudity instead of just ‘depantsing’.

Previously in this series, we cited David Mamet’s assertion that “the correct study of the dramatist was neither his own feelings, nor those of the actors, but the attention of the audience.” Reviewers are certainly part of the audience, but I believe they need a different framing in considerations of self-producing. When we heed icons like Sarah Bernhardt stating that “The theatre is the involuntary reflex of the ideas of the crowd”, we should acknowledge that there is a segmenting in the crowd. Audience members do not all come with the same mindset. There are those who know our work and have returned, there are those who only know us and finally have decided to see one of our plays, there are those with whom we are unacquainted who have come to this particular play based upon some recommendation or report, there are those who came because it was a free ticket because US producer are wisely papering the house in preview week, and there are reviewers. We can roughly categorize each of those groups as arriving with a different mindset and even individual peculiarities, but the reviewer’s disposition merits a more specific examination. So, scroll a little further.

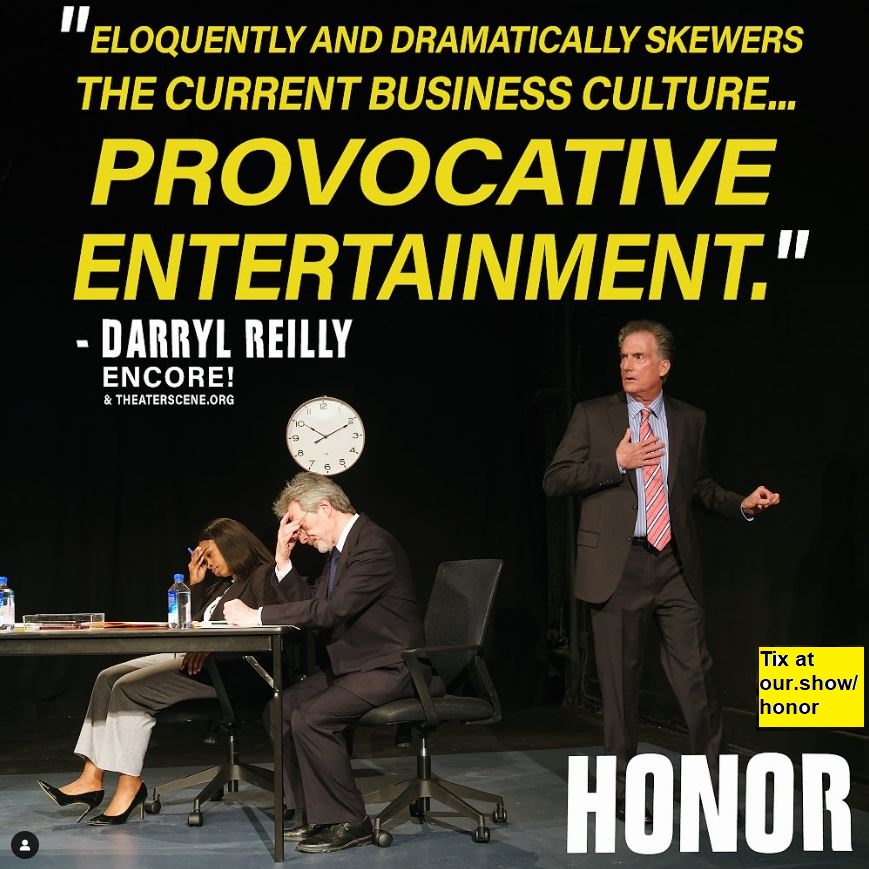

Your reviews aren’t all going to be like these.

Like any other member of the audience, a reviewer is going to project their own lives and experiences onto what you have written. And unless your play is Our Town, its content likely focuses on a particular dimension: families, workplaces, wars, etc. how will that work appear to audiences that have different experiences and perhaps no familiarity at all with the world of your story? Although you would already have these concerns as a playwright, you as the producer also have additional worries as to how viewers react to their work. After the first week, word-of-mouth especially in its contemporary version of posts and comments on social media platforms assumes a criticality in attracting audiences. And people do read reviews. There are dozens of little websites in the New York City metropolitan area for example that publish reviews of plays. Some of them have a specific theatrical emphasis and others or more general appealing to senior citizens or residents of a particular neighborhood. Getting reviews means getting attention, credibility, notice. But what you do with reviews is important not only for your success but also for your sanity. (Especially true for the actors reading this as Tom Briggs suggests here.)

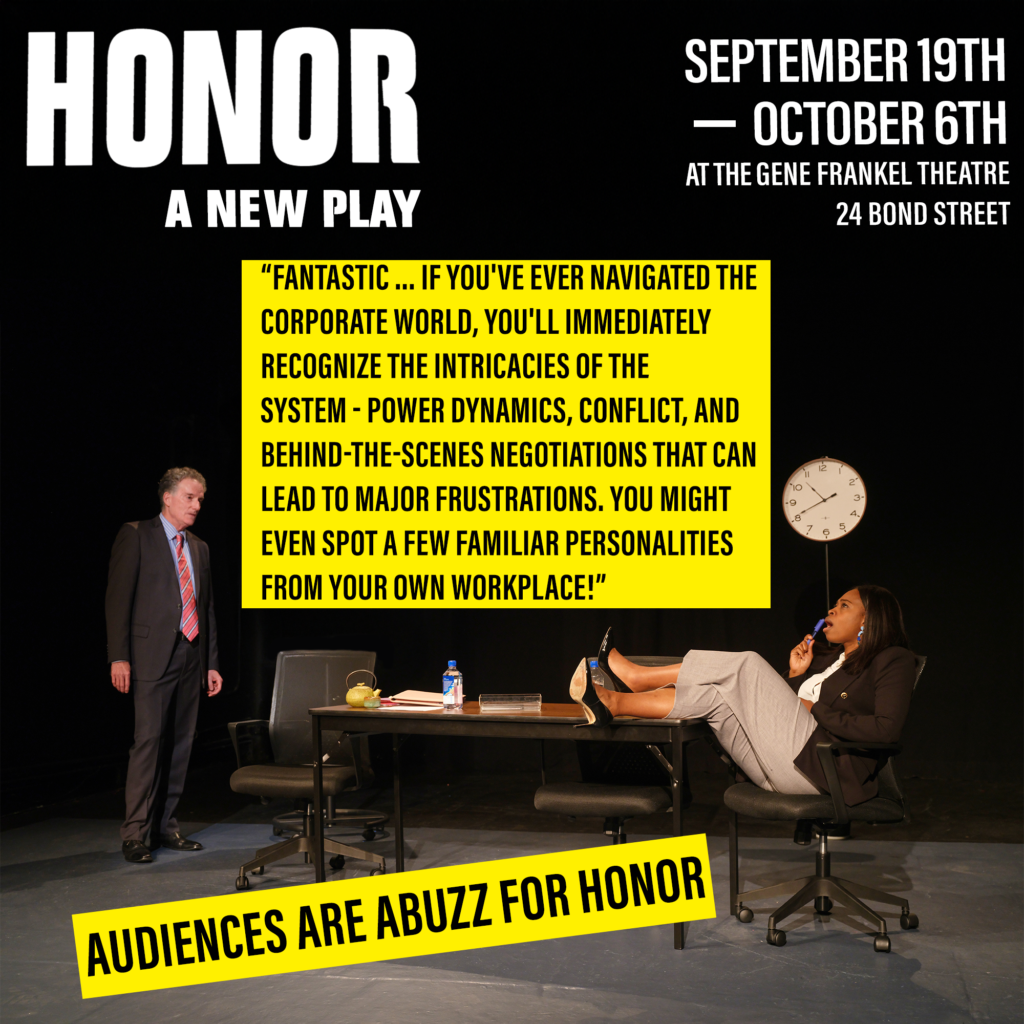

Why impose this qualification? Because not all of the people writing reviews have a background in theater, dramaturgy, or even entertainment. Your reviewer might have spent their whole life as a dancer and political activist and your play is about the corporate world. That likely will result in a different sort of review than if your reviewer had to deal with bureaucracies because of their straight job or even just because their host organization is large enough to have such structures. Similarly, if your reviewer has spent most of their career as a financial analyst then you’re going to have that worldview seep into their opinions about your play.

Will this appearance of reviewers with limited or stilted experience matter in every situation? Probably not. Our first production, alms, which we unwisely mounted without any PR, publicity, or marketing advice didn’t get any reviews even though it sold out all of its performances. We learned from that circumstance and budgeted for the kind of consultation that does get you reviews. And in some cases, they have been uniformly positive. We still think it’s important not to pay to much attention to them.

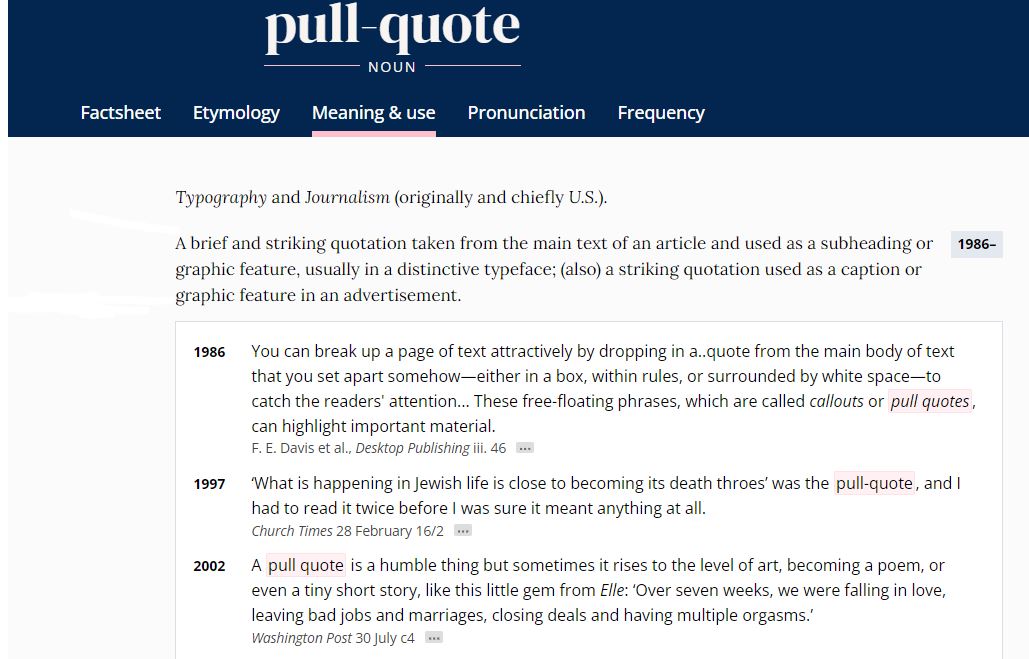

But what if the reviews are missing the point? Our approach is simple: the only thing I want from a review is a pull quote. It doesn’t matter whether they like what I have written or hate it or misunderstand it. The job of a self-producing playwright is to find the most positive phrase you can and use that in your advertising. This is a long-standing practice of producers in movies and theater; check out this 1987 LA Times piece on the ploy. In fact, there was once a controversy in which the New York Times complained that quotes were being taken out of context.. (For more on David Merrick including his scheme to find people with the same names as prominent reviewers to offer their positive opinions, scroll down within this article and this one that are very good surveys of the effect of reviewers upon audience size.)

DISCLAIMER #2: I have practiced the art of the selective pull quote. (Apparently, this is not a good idea to do if your play is opening in the EU according to this 16-year-old Guardian article.) At the end of our week run, we received a review that was… less than affirming. We weren’t going to use it in marketing anyway because all of our ad and publicity budget was gone, but we did use it in a post. Nothing in the review seemed usable, but our wonderful PR guy Ron Lasko at Spin Cycle disagreed when I told him that. Here’s the review and here’s what Ron selected:

Compelling… The strengths of the play lie in its situation, its

Show Showdown

embrace of ambiguity, and its recognition that people are, well,

people.

Pretty nifty. And anyone who wants to read the entire review from that source can certainly get the catalogue of weaknesses that were identified. I offer this additional way of looking at self-producing in the same spirit that informed the original compilation of thirteen: we need to make theater live. That takes talent and guts. There may be reviews that are negative and yet in some way accurate, and we will learn from those along the way. But not while we’re in the process of trying to put audiences in front of our actors and vice versa. We all would to our team to do the best we can and then absorb the learnings as to how we can do better.

Practice the art of the pull-quote with your reviews and don’t let them pull you down. But do let us know what you think as a self-producing or other kind of playwright. We’d love to hear and read your considerations on this subject.

PS Here’s what ChatGPT said about our play; AI is more sophisticated than I imagined considering they didn’t actually pay for a ticket or show up even to claim a comp.