Opinion by T.J. Elliott

The earliest known use of the phrase ‘love-hate relationship‘ in the English language comes from a Joan Riviere’s 1925 translation of the Collected Works of Sigmund Freud. Obviously, many other stimuli had elicited a love-hate reaction long before Doctor Freud used the German ’Liebe-Hass’ to try to explain how screwed-up we all are. Bureaucracy, older both as a word (coming this time from the French) and as a system of authority (predating Christ and Buddha), is likely in the top ten of love-hate targets alongside destination weddings and the New York Jets. The antics of Elon Musk and his elves seeking to create a new structure for the federal government’s operations look like classic hate-love; detest and destroy what existed before January 20th, but love what they are attempting to install, a Next-Gen bureaucracy.

Our South African autodidactic continues a long tradition of faultfinders of whatever is the current bureaucracy. Complaints on cuneiform tablets etched 3800 years ago in Babylon document that even then haters were gonna hate a system of administration by a hierarchy of professional administrators wielding procedures, routine, and rules over others. But those same whiners likely loved some inventions that such officialdom supplied under the reign of Hammurabi: the wagon wheel, plow, and sailboat along with calendars, levers, pulleys, and even ziggurats. Who doesn’t fancy a good ziggurat?

Classic Art Wallpapers (CC BY-SA)

Even though Americans might not use the B-word when often unseen pen-pushers give us regularity quality in benefits such as Social Security payments, college loan programs, organic food certification, and child resistant packaging rules (okay, maybe not last one), we like those effects. But when those same functionaries chosen supposedly for their technical qualifications employ rules, regulations, budgets, statistical reports, and performance appraisals to regulate our lives in ways that thwart our desires and burden our time then we hate bureaucracy.

My experience — not always successful — as a former bureaucrat (I was Chief Learning Officer at Educational Testing Service — ETS — in the last 20 years of my ‘straight’ career before returning to playwrighting) discerns that Elon Musk will create a disaster with his hatred of the present federal bureaucracy and Next-Gen aspirations. This doom sense is also informed by my previous decade as an organizational consultant tinkering in other people’s bureaucracies; again, not always successful. My immersion in those red-tape worlds confirmed their tendency to frustrate minds, weary bodies, and deaden souls. Indeed, I recounted the good and the bad, which I viewed and sometimes orchestrated, as part of a recent BBC documentary, Bureaucracy – what is it good for? And who is it good for?, hosted by my sometimes playwrighting collaborator, Joe Queenan, and produced by Miles Warde. I don’t speak until thirty-eight minutes into the program, but classicist Professor Edith Hall earlier traces usefully the ‘das Gute und das Schlechte’ of bureaucracies back to Ancient China and Greece. Professor Hall suggests with bureaucracies that it’s always been Liebe-Hass all the way down the line.

What renders bureaucratic love hate relationships much more complicated than Elon seems to understand is that so many of us make our money today by being part of bureaucracies: financial services companies, medical institutions, insurance behemoths, tech titans, and good old government. With the bureaucracies we encounter, the reality is as Dire Strait sings, “Some days you’re the windshield, some days you’re the bug.” But when it comes to what is probably the largest and most influential bureaucracy in American life — the Federal Government — all of us at one time or another are going to be the bug. That’s why the changes underway in that entity should interest all of us no matter what our vote was last November. Are Project 2025 pretensions hybridized with Muskian noodling more like what Hammurabi originated in Babylon or what Martin Bormann cooked up in Berlin during Germany’s transmutation of its bureaucracy in 1935? Are we getting the 21st Century version of a life-changing plow or getting plowed under? So far, Next-Gen is looking Germanic.

One of the most insightful witnesses of that societal deformation in Germany was Hannah Arendt. In her 1970 book On Violence, she came down more on the hate or hass side of the equation regarding bureaucracies:

The greater the bureaucratization of public life, the greater will be the attraction of violence. In a fully developed bureaucracy there is nobody left with whom one could argue, to whom one could present grievances, on whom the pressures of power could be exerted. Bureaucracy is the form of government in which everybody is deprived of political freedom, of the power to act; for the rule by Nobody is not no-rule, and where all are equally powerless we have a tyranny without a tyrant.

Everyone is quoting Hannah these days. Comments from this eminent authority on authoritarianism (and our current executive branch doesn’t even bother denying its aspirations in that direction) appear both prescient and depressing. But this perennially pertinent philosopher also had a lot to say about bureaucracies as elements of totalitarian societies. Thus it seems highly likely that she would recognize the current efforts of the so-called Department of Governmental Efficiency or DOGE as a realization of her prophecy above although she might not smile on my assignment of ‘Next-Gen’ to it.

But Next-Gen seems particularly apt for this phase of bureaucratization as the phrase first appeared in an article on gaming console systems in 1995. That association of technology, coolness, and even nerdish superiority wafts about any declaration of some invention as not just ‘next’ but residing in a stage distinctly beyond where most of us currently operate. Next-gen as a label for the present capricious coup with more than a whiff of Mark Zuckerberg’s ‘break things fast’ mantra fits the aim of the current executive branch: the acceleration of their reformation of bureaucracy into what seems gauged to meet Arendt’s model of ‘a fully developed bureaucracy’. Applying Next-Gen to this development should also remind us of how often the promises of improvement for some product never materialized including for Mr. Musk. For those of us familiar with bureaucracy from inside and out, up and down, as victim and villain, this development carries the potential for disaster even beyond what Arendt predicted.

This is not to say that current generations of bureaucracy in their efforts to organize human activity so as to maximize efficiency including the one being disemboweled by the

Elon-inator are faultless. Bureaucracies have always been about control; often in restraining and checking behaviors they create conflicts with human beings who want what we want when we want it, not to be put on hold, or a list, or steered to a satanically and/or sloppily designed website. But Musk isn’t changing the control part of the federal civil service and it’s agencies. What will emerge from this Godzilla attack will still be about control; it will just be harder to figure out who “the man… who pulls the wires” will be is as that ardent bureaucracy hater John Stuart Mill wrote in 1837. That’s to be expected. It is the unintended consequences Trumpian licensed tumult in that sector that now alarm veterans of organizational labyrinths.

As Richard Sennett noted 45 years ago in his book Authority, the higher the perch of an official in a bureaucracy, the more autonomy enjoyed. When the actions come with presidential license and billionaire guidance, the perch can neither get much higher nor the autonomy much greater. Sennett pointed out that, “autonomy removes the necessity of dealing with other people openly and mutually.” This control allows a distance between bureaucrat decisions and those affected by them. In this next-gen bureaucracy where according to a trenchant analysis by the Washington Post: “The end goal is replacing the human workforce with machines. Everything that can be machine-automated will be” the distance from actual people might be absolute. We are headed to Arendt’s forecast of a bureaucracy where “there is nobody left with whom one could argue, to whom one could present grievances, on whom the pressures of power could be exerted.”

Previous federal administrations at least since the Pendleton Civil Service Act in 1883 tweaked the existing bureaucracies as they contended and negotiated with the prevalent culture, that is, the way things are done around here. The expectations of any new regime — no matter their ideology —stayed within a standard deviation of what was an agreed-upon normalcy in placement of authority. Those expectations of what was fitting for government degraded in the last ten years — the rise of Trump since 2015 is not a coincidence — and now the federal bureaucracy is under bombardment. (History buffs will recognize one precedent in this behavior: the Tenure Act of 1820, which almost guaranteed that each new president would be able to throw out all of the officials of the previous administration.) The way in which this administration has acted in its first month is not just illegal but also antisocial, and the latter aspect is perhaps more important. Hannah Arendt is relevant yet again: the danger is that any new bureaucracy like this one expressly designed to serve and obey all of our capitalist forces will ‘left to its own devices ha(ve) a tendency to raze all laws that are in the way of (its) cruel progress.… (ignoring) the misfortune of other people.”

Some readers will shriek that in focusing on what is happening to the bureaucracy, I am criminally missing the bigger issues of degradation of our constitution, the fomenting of white supremacy, and stomping of human rights. Guilty. Strange as it is to admit on social media, I lack the qualifications to opine usefully on those very serious issues. Others, especially apologists and lickspittles for Trump redux, will wave away my — and Hannah’s — judgments as overreaction to what they consider mere modifications. Blithely referencing The Who lyric: “Yeah, Meet the new boss. Same as the old boss”, they see nothing untoward in Musk’s machinations. Fervent Trump and Musk fans like Shervin Pishevar will see this Next-Gen bureaucratization as a necessary razing of a “rotting structure.” But I doubt that many of these observers actually have experience making changes in organizations. My familiarity with such initiatives suggests the speed and depth of changes to the existing bureaucracy will prove dangerous. The core lesson in that work is to adopt the attitude of a bomb disposal expert: be very careful about what wires you snip so the whole thing doesn’t explode. I’d much rather be writing a play than an essay the dangers of being a buttinsky to our federal bureaucracy, but if this ‘bomb’ explodes all of us risk injury: financial, medical, communitary, and even physical.

The possible perils fall into two categories: rising resistance and disappearing decision-making. Regarding the former, my work with a variety of companies and nonprofits led me to form a maxim: all organizations resist change but complex organizations resist change in complex ways. There are few organizations on this planet as complex as the federal government. That bureaucracy comprises cabinet departments, government corporations, independent agencies, and regulatory commissions carrying out laws and providing essential services to the public. There’s a lot of different colored wires in that bomb. If you thought quiet quitting was bad wait until you see slowed down civil service. Departments depend upon one another in our government and delays in one area will log–jam bottleneck, and block communications and decisions so that services even Trump supporters care about will suffer delay or worse. You can only jury-rig and makeshift the machinery of government so much before its outputs diminish or cease appearing at all.

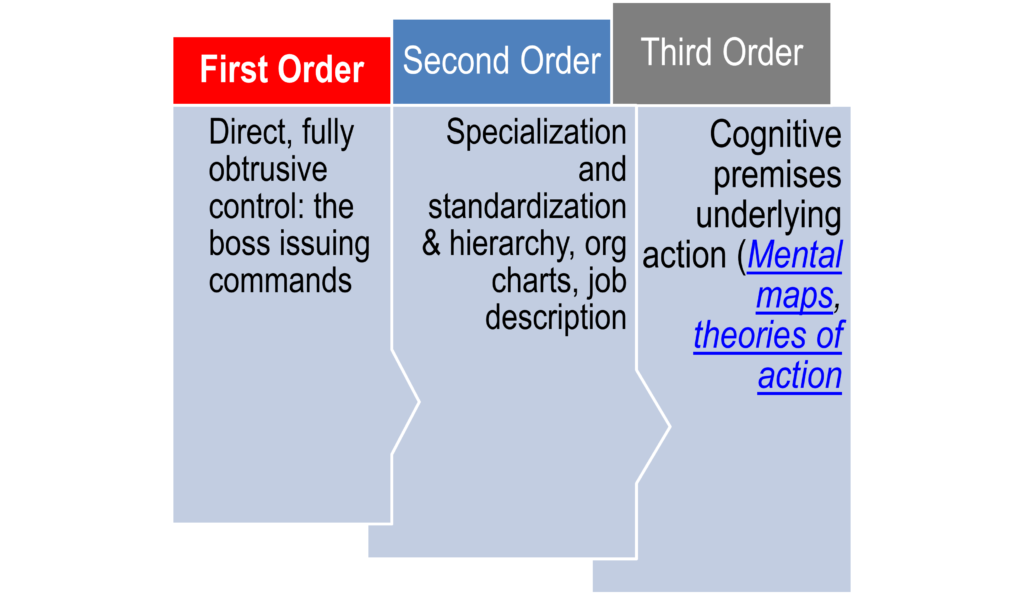

But the other set of perils should concern us even more. Elon’s eccentric emendations will make us less able to deal with emergencies. Tesla waving away a self-driving car killing people is nothing compared to a government failure in responding to some emergency harming many citizens. Why might that happen? The answer lies in looking at how the structure of bureaucratic control works. A good model for understanding this dimension of organizations is Charles Perrow’s three orders of control.

- First Order: Direct, fully obtrusive control such as getting orders, direct surveillance, and rules and regulations; (Think the boss yelling commands, a supervisor referencing a manual, the designated flows of information like reports to management so that they can yell different commands)

- Second Order: Bureaucratic ones such as specialization and standardization and hierarchy, which are fairly unobtrusive. (HR enforcing organizational charts, job descriptions, performance metrics that may or might not match what the boss is yelling)

- Third Order: Fully unobtrusive ones, namely the control of cognitive premises underlying action (Mental maps, theories of action, shared beliefs & values, ‘the way we do things around here’: the things that guide workers in producing results no matter what commands the boss yells)

Elon’s echelons will replace First Order players or menace them into submission. In doing so, those interlopers may gain power to some extent over Second Order controls by switching out the standards and hierarchy. But the Third Order will prove to be trickiest and least immediately susceptible to the radical changes wrought in departments and agencies. Why? Perrow’s third-order controls are not written down somewhere so you can shred them. These controls reside in each department or sub-departments’ norms, culture and language. Despite their manifestations in forms, logs, and procedures, Third Order Controls are like the water in which a fish swims: necessary and unnoticed until it disappears.

Charles Perrow, in his book Complex Organizations pointed out that third order controls shape our reality and thus the premises of our decision-making in unobtrusive ways; added comments in bold:

- They limit information content and flow, thus controlling the premises available for decisions [There is a general agreement about what is important to notice while doing your work because noticing everything is horribly inefficient]

- They set up expectations so as to highlight some aspects of the situation and play down others [See ‘1’ General agreement about what is important to do while at work shapes not just the day, but avoids confusion and wasted time]

- They limit the search for alternatives when problems are confronted, thus ensuring more predictable and consistent solutions [Having a mental map of how things are supposed to work keeps you from ‘reinventing the wheel’, or worse, go from the wheel back to the sledge]

- They indicate the threshold levels as to when a danger signal is emitted (thus reducing the occasions for decision making and promoting satisficing rather than optimizing Behavior) [Again, mental maps quickly identify what is portends trouble]

- They achieve coordination of effort by selecting certain kinds of work techniques and schedules [See ‘2’]

Organizational consultants have long recognized that these controls can have positive and negative effects. Sometimes the environment has shifted and the Third Order controls including the mental maps have stayed the same. (Musk could argue this is the case with the federal government, but he hasn’t. Instead, he’s trying to change the environment.) Then Third Order controls make change more difficult especially if those intervening underestimate the power of habit, training, socialization, routine. But these controls also help to keep things running and, more importantly, underlie successful responses to emergency events. Think of the work reality of a mechanic on an aircraft carrier, an operator on a food processing line, or a nurse in ICU. When things go sideways, we rely upon them to not only notice but also quickly address that shift. Messing with their organization can mess up their ability to respond successfully.

Another problem that might arise with this intervention is that the best version of these Third Order controls sometimes exists only in the heads of certain key people, not necessarily the ones who are most favorably situated within the organization chart. They are the people that others with less experience but often more formal authority seek out when a wicked problem arises. Get rid of those people or severely demotivate and demoralize them and you change the way in which everyone in that area makes sense of the world; an alteration that will have disastrous effects if they’re trying to make sense of something that is unusual, unexpected, untoward.

Karl Weick described the critical role of third order controls in the sensemaking process that occurs in the moment of an accident or catastrophe:

”Either culture or standard operating procedures can impose order and serve as substitutes for centralization. But only culture also adds in latitude for interpretation, improvisation, and unique action… This is in sharp contrast to centralization by rules and regulations or centralization by standardization and hierarchy… Furthermore, neither rules nor standardization are well equipped to deal with emergencies for which there is no precedent.”

In blunter terms, the shit does hit the fan in every organization sooner or later and those who have shielded others from those effects in the past or even figured out how to limit the mess constitute an advantage for the rest of us standing upwind. In taking out those people who are good at ‘interpretation, improvisation, and unique action, and replacing them with machines, you lose that advantage when the next poop event occurs.

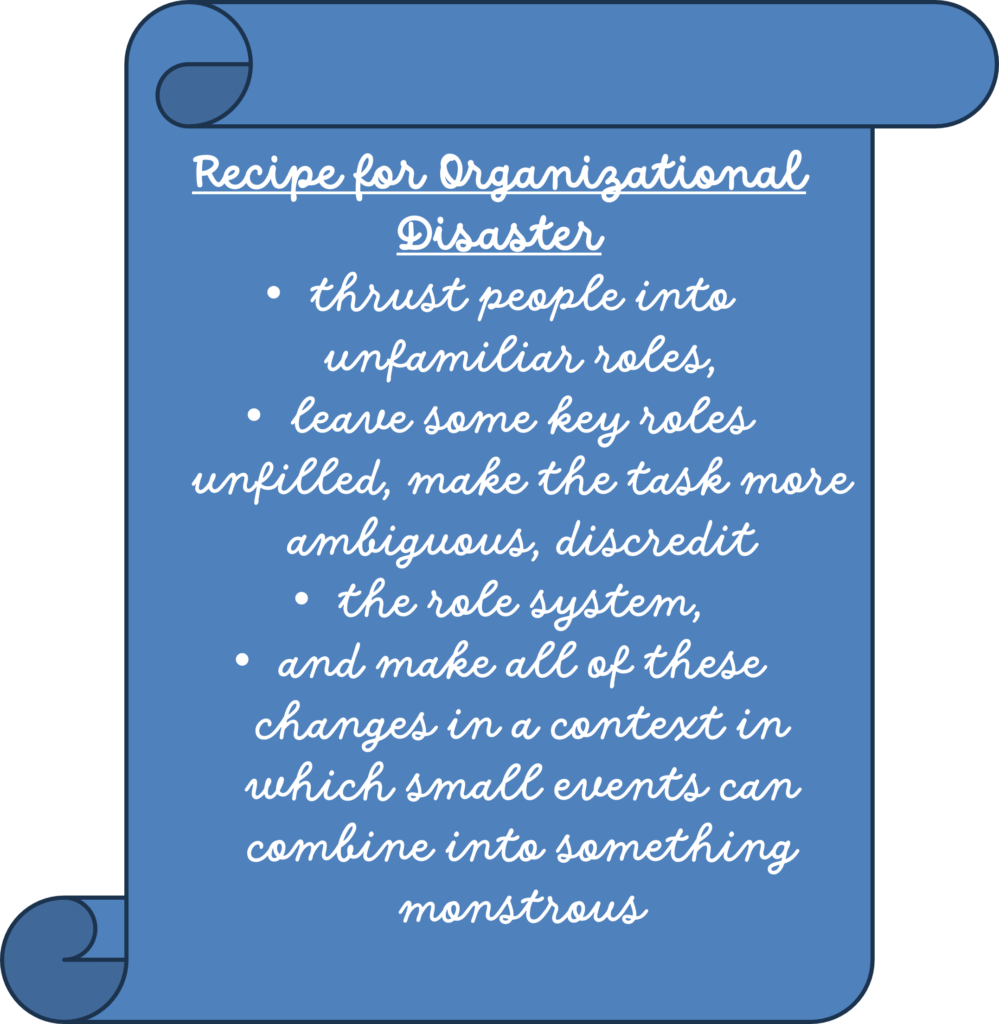

Karl Weick wrote using the Mann Gulch fire disaster as an exemplar of those times when things fall apart in an organization’s operation, when Standard Operating Procedures or refined Large Language Models will prove not just insufficient but dangerously wrong:

“What holds organization in place may be more tenuous than we realize. The recipe for disorganization in Mann Gulch is not all that rare in everyday life. The recipe reads, Thrust people into unfamiliar roles, leave some key roles unfilled, make the task more ambiguous, discredit the role system, and make all of these changes in a context in which small events can combine into something monstrous. Faced with similar conditions, organizations that seem much sturdier may also come crashing down, much like Icarus who overreached his competence as he flew toward the sun and also perished because of fire.” [i]

This recipe for disorganization bears repetition: thrust people into unfamiliar roles, leave some key roles unfilled, make the task more ambiguous, discredit the role system, and make all of these changes in a context in which small events can combine into something monstrous.” Doesn’t theactual plan of the DOGE dodge go 5 for 5 on that list? Machines replace people but some of those people know when and how to lose the current strategy, ditch the usual decision-making, and expand to a different way of sense-making. This is the secret strength of bureaucracies; somewhere within the labyrinth a person or persons sits with the talent and intuition to make sense of the senseless, to check the unexpected. They will utilize a set of contingencies first to understand what the organization is facing and then to adapt, escape, or solve that situation. Elon deals from success cases; what you need is a system to handle paradox, uncertainty, and failure. By the time, the machine learns from the next unexpected event or unseen mistake, it’s too late. Government in that scenario has failed in its essential mission of protecting its citizens. Weick and Roberts in their 1993 exploration of sensemaking in dangerous occupations cited the primal advice of mechanics on aircraft carriers: “Never get into something you can’t get out of.” We are tottering tyrannically toward a circumstance we can’t get out of.

And there is another aspect to this initiative — hate unbalanced by love — that may lead to even worse consequences. Elon and his minions in their burning desire to create a federal system they can dominate also detest the people who are the object of their dismantling. The architects of this new order want the destruction of civil servants, not their well-being. Their wish for a new world blends with a hatred of those they deem either antagonistic to that vision or just bad fits for the new techno-plutarchy. This vehemence of their enmity —a true hate- hate relationship — will make all of the negative consequences listed above even worse by shutting down any consideration and course correction while inciting secret retribution schemes and even sabotage. Hatred always worsens decision-making and execution. Trying to change quickly and heedlessly what has served us so well in a USA to which immigrants keep coming and in which billionaires keep getting richer could mean that what starts out as next-gen bureaucratization could turn out to be last-gen. No one will love that.

[i] The Collapse of Sensemaking in Organizations: The Mann Gulch Disaster Karl E. Weick . Reprinted from The Collapse of Sensemaking in Organizations: The Mann Gulch Disaster by Karl E. Weick published in Administrative Science Quarterly Volume 38 (1993): 628652 by permission of Administrative Science Quarterly. © 1993 by Cornell University 00018392/93/3804-0628.