My ur-source on self-producing and so much more has died. Requiem in pace, frater meus

It’s March 4, the launch date of 13 Ways of Looking at Self Producing co-authored by Gifford Elliott and T.J. Elliott — me. (The 4th of March is also the day when the Unites States Constitution went into effect. ‘Ha ha ho ho hee hee’ as Tom Robbins used to say.) According to our carefully calibrated project plan, this is the day when we are supposed to send into the electronic universe our Starfleet of blurbs and come-ons even though we know most of them will end up crashing on uninterested (uninhabited?) minds or otherwise sucked into the black holes of social media. And even with that foreknowledge of the futility of advertisement, Gifford and I will launch a thousand ‘ad-ships” tomorrow. But not today, definitely not today. Because my friend of over fifty years Michael McKeever, the long-haired blond lad with the halo above in 1972, died yesterday. It’s time for praise not promotion, memorials not memes.

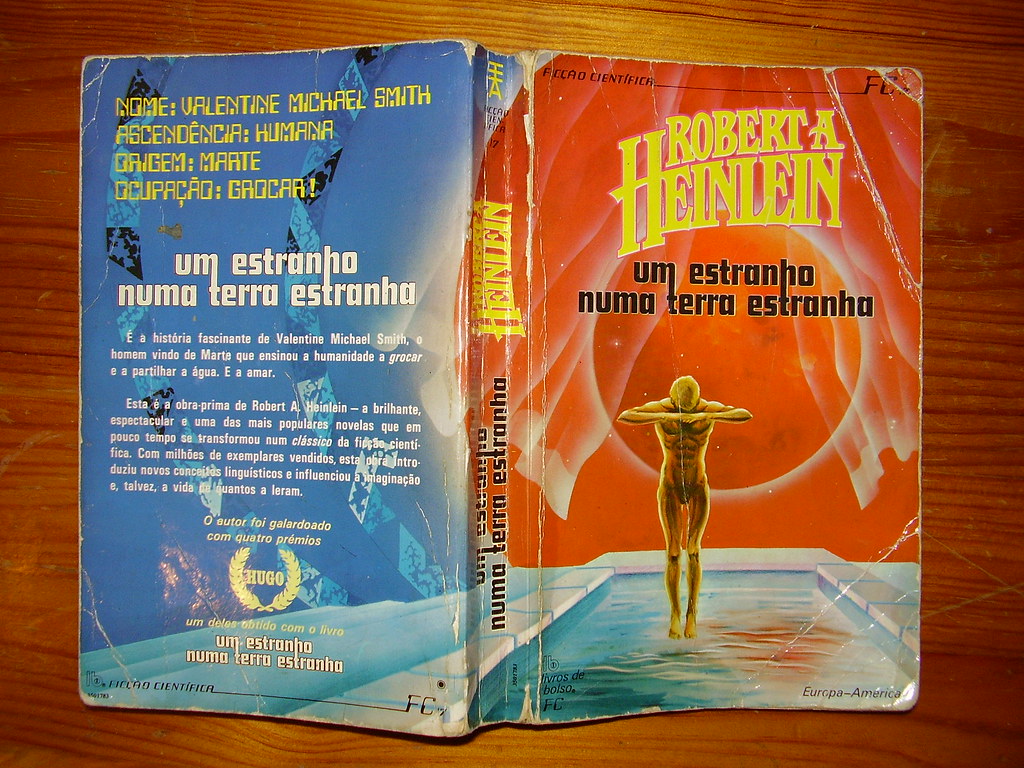

I want people to remember McKeever if only for a moment, and even though he was a man who deliberately parried all attempts at draping any recognition upon him. In trying to grok (a word McKeever favored from Stranger in a Strange Land, a label that fit Mac too) all of the emotions and thoughts flowing around this loss, I’m also laughing at the weird coincidence — and trust me, McKeever was the midwife of many a weird coincidence — of this death coinciding with the launch day for a book in which I offer (along with my collaborator Gifford) contemplations, lessons, and admonitions about self-producing theater. I don’t know if McKeever in his last months took a look at any of the source material for the book, which was previously blogged here. I doubt it. His nature was to stave off any mention of his many good deeds, and we made a big deal in our series out of what he taught me about self-producing and myself.

In the summer of 1972, McKeever at 22, the acknowledged and beloved hotshot of our theatrical community and my roommate in the top bunk wedged into our garret apartment, picked me to be co-producer of a touring production of Waiting for Godot. I was also to play Pozzo. Yes, the hubris of the young: a 20-year-old playing Pozzo. For those readers who amazingly have never seen Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot and can’t wait for the upcoming Keanu Reeves version (not a joke), a query to AI this morning states resolutely that “Pozzo symbolizes the arbitrary nature of power and authority, as well as the meaninglessness of human roles.” Obviously, the perfect role for somebody still so wet behind the ears that I dripped. I was told, however, that I was rather good at portraying this bombastic speechifying figure. At the time, I chalked up my ease in expressing things dramatically as probably emanating from trying to get attention at a crowded, noisy, sometimes contentious, always comic dinner table as the youngest of 5 boys. (McKeever was the 2nd of 13 children out of East Falls in Philadelphia and his voice was godlike.)

Or my acting success then could be because as one ex-girlfriend of the time said that I already embodied how her study guide described the character: “Pozzo is tyrannical, cruel, focused only on himself.” Typecasting or tight acting, it really didn’t matter to me as long as people said I was good.

But nobody told me that I was good at being the co-producer of that play. And there’s good reason for that because I sucked. In the end, I did enough — barely and often badly — and McKeever did everything else not only to avoid disaster but to make the tour a success. But the most important learning of that time not just about self-producing but about how to occupy my existence was when McKeever had the equivalent of an after action review with me a month after we closed not in New Haven but at an all-women’s Catholic college in the leafy Riverdale precinct of the Bronx. He had kept a list of everything that was done, undone, redone, dropped, forgot, and fucked up. I sat there and took it all in. And then he asked me with that blade of a grin, “Tell me, T.J., are you running your life or is your life running you?” That, my friends, is what is known as a rhetorical question attached to a dropped mic and a hand grenade. It changed my life. He changed my life by making me see in one simple equation my misdirection. I didn’t reverse the running of my life immediately, but that’s because life is much harder and slower to turn around than an ocean liner, a starship, or a conspiracy theorist. But that navigational imperative buried in his question started my ‘coming about’, my ‘tacking’ into the winds of the world so that I could reach the jobs, marriage, and satisfaction I wanted including successfully self-producing plays less than a decade later in New York City. The lesson was so important that I enlarged it over the years in my straight jobs and taught it to execs as The Employment of Failure. McKeever had tattooed that advice on my brain: if you want to make something that matters, you start with the making, the shaping, the refinement, the education of yourself.

I came across his wisdom in the words of many others over the years especially Bob Kegan and Lisa Lahey up at Harvard where their theory on adult development produce some very specific exercises in which participants question themselves on what they are doing or not doing that keeps them from achieving their stated desires. I thought it pretty cool that McKeever had figured out that principle and communicated it to me so effectively in 1972. He was much more to me and others, however, than that moment. He was a beloved brother and uncle to that McKeever brood. Mac went on to become a celebrated teacher at Girard School in Philadelphia while still acting in a variety of community theater productions. He told me that he felt better suited for a primary task of service then a profession of acting. I saw him in many plays over the years and last June we got together for the 50th reunion of that production of Godot. And he still sparkled as Estragon. Now his sparkling will be in the sky. As rich as he made me with those words so many years ago, so poor I feel now at not being able to see him, to hear him in person again.

Estragon

In the meantime let us try and converse calmly since we are incapable of keeping silent.

Vladimir

You’re right, we’re inexhaustible

Estragon

It’s so we won’t think.

Vladimir

We have that excuse.

Estragon

It’s so we won’t hear.

Vladimir

We have our reasons.

Estragon

All the dead voices.

Vladimir

They make a noise like wings.

Estragon

Like leaves.

Vladimir

Like sand.

Estragon

Like leaves.

Silence

Vladimir

They all speak it once

Estragon

Each one to itself

Silence

Vladimir

Rather they whisper.

Estragon

They rustle.

Vladimir

They murmur.

Estragon

They rustle.

Silence

Vladimir

What do they say.?

Estragon

They talk about their lives.

Vladimir

To have lived is not enough for them.

Estragon

They have to talk about it.

Vladimir

To be dead is not enough for them.

Estragon

It is not sufficient.

Silence