Recently, my attention in these writings focused on rebutting the prevalent notion among the punditocracy of the left (center, far, handed) that the problem with the corruption, unconstitutionality, and general havoc of the current federal government our electorate chose came about because a certain large segment of our citizenry were bedeviled and bewitched by misinformation. That supposition then begat a notion blaring like a dead smoke alarm battery from these cognoscenti that if only we could get ‘them’ the right information everything would change. My take is that the kinds of choices involved in elections – attendance at rallies, campaign contributions, voting for someone or NOT casting any ballot – arise more out of a person’s attitude and not from a reasoning process. Want things to change? Figure out how to change people’s attitudes, which as I point out in those writings is VERY different than any other kind of learning.

That stance does not preclude an appreciation for what reasoning can and does accomplish in our lives. An irony of our current sociopolitical circumstances is the preponderance of agitation, bombast, snark, and snarl at a time when the current administration seeks to dismantle both the process and effects of reasoning in our lives in order to achieve their objectives. A government report citing non-existent studies, a misleading tariff chart, an images of ‘Genocide’ in South Africa that was from the War in Congo. You get the point. The veracity of a claim seems not to matter. Indeed, claims don’t matter in this moment.

No. No. NO!!!! Claims matter. And the person who generously, kindly, superbly taught me so much about claims sadly died last week: Bob Mislevy. We met during my time as Chief Learning Officer at ETS. Bob returned there for a second stint in 2011 but his work was always central to the world of educational measurement in the 21 Century. If anyone wanted to understand where assessments should go in order to be maximally helpful to learners and educators, they had to encounter and comprehend the key concept that Bob and other ETS colleagues, Russell Almond and Jan Lukas, devised called Evidence Centered Design, a way of thinking about testing founded on the ancient notion of claims.

If evidence sounds like an element more associated with criminal law or philosophy then you’re onto what Bob discrened. But he connected them to testing because evidence is what we need from the best designed tests as well.

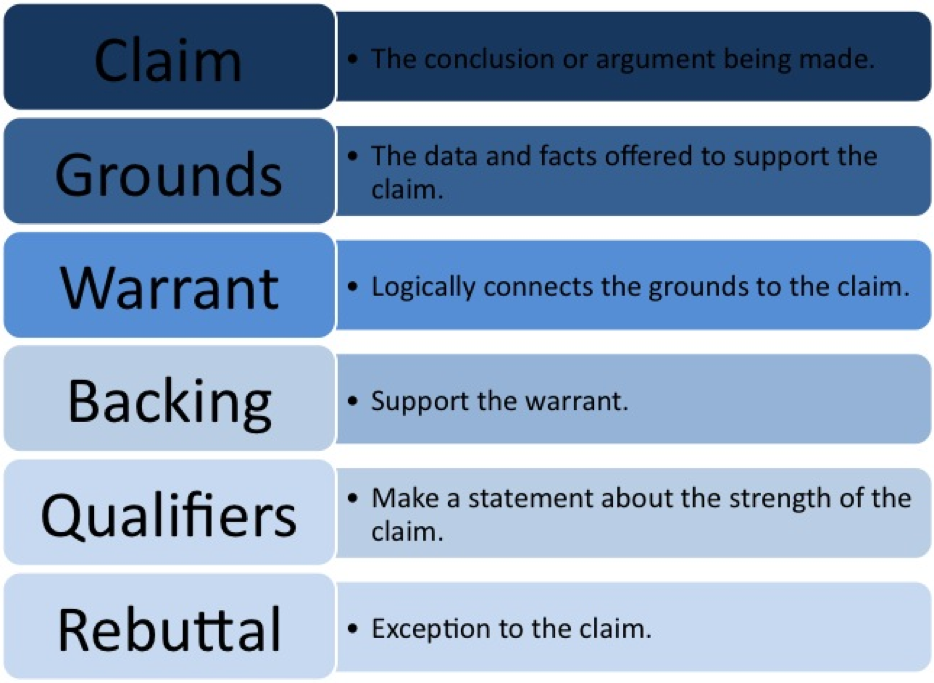

And he used the best sources to create this new foundation for better assessments. John Henry Wigmore pioneered the analysis of legal evidence in trials in order to make claims of guilt or innocence. Stephen Toulmin “sought to develop practical arguments which can be used effectively in evaluating the ethics behind moral issues.” David Schum studied the “properties, uses, discovery and marshaling of evidence in probabilistic reasoning” for professions such as intelligence analysts. (Schum was particularly interesting since one of his lines of evidence was “the use of love letters as crucial evidence in a murder trial.”) Toulmin, a British philosopher, explaination of what a claim is and its need to be able to pose an argument insoired Bob to take a similar approach to assessment. As Toulmin wrote: “A man who makes an assertion puts forward a claim — a claim on our attention and to our belief … just how seriously it will be taken depends, of course, on many circumstances… whatever the nature of the particular assertion, in each case we can challenge the assertion, and demand to have our attention drawn to the grounds (backing, data, facts, evidence, considerations) on which the merits of the assertion are to depend. We can, that is, demand an argument.”

John Henry Wigmore looked at claims in a legal context. His 10-volume Treatise on the Anglo-American System of Evidence in Trials at Common Law (1904–05), usually called Wigmore on Evidence, is one of the world’s most important books on law. If a court was to establish guilty or not guilty, liable or not liable, it was making a claim and doing so meant gathering, examining, and judging evidence for one or the other of those positions. Evidentiary reasoning provides a coherent framework for making claims instead of making things up or just making a mess.

When it comes to the claims we make — or are made about us — in everyday life, evidence often fails to receive appropriate attention. We think much more about the score or outcome (getting into a particular school, snagging an A grade on an exam, being awarded a job) than we do about how it was derived. As Bob Mislevy noted in a 1994 paper discussing Wigmore at length, “there are multiple routes to an outcome, and observing the outcome alone does not indicate the route.” In the most useful sorts of processes that end up producing claims, we should want evidence not only of what someone knows or can do but of how they are able to use that knowledge in order to accomplish the tasks that constitute the assessment.

Bob was able to extend and apply to assessment the concept of claims — their utility and value — from these disparate domains of logic, criminal courts, and probability. For example, Bob with Russell and Jan (and a whole bunch of people afterwards) started from the premise that the purpose of any test is to make a claim. As the trio wrote in the introductory paper on Evidence Centered Design (ECD) “What all educational assessments have in common is the desire to reason from particular things students say, do, or make, to inferences about what they know or can do more broadly.” In other words, clarifying that an assessment was a claim was saying that we as a society needed to think differently about how we were testing kids of all ages. What were we claiming? Would it stand up as claims from law and science did?

Building upon another ETSer Sam Messick’s construct-centered approach to assessment Mislevy’ s work around evidence-centered design allowed ETS to develop unique expertise in creating frameworks to guide assessment development. Properly working as the non-profit is was and is, ETS shared this knowledge worldwide under the organizational leadership of R&D SVP Ida Lawrence and CEO Kurt Landgraf. Those frameworks could be used to operationalize constructs in a way that fosters the connections among assessments, teacher development, and student learning. They could even advance efforts distilled in my personal rallying cry: No test but for learning! Make the evidence to support a claim about a learner the actual work they did in class and not some snapshot in an end of year exam. Create a loop of information that would guide and shape the instruction for each student. It didn’t happen then for a swarm of reasons including the expense involved to build out the infrastructure needed just to be clearer about what exactly were the claims schools would want to make. But that doesn’t mean it couldn’t happen. And if it ever does, Bob’s work would be at the foundation of such a valuable invention.

…

Bob Mislevy and his co-author Michelle Risconcente were clear that more transparency was needed in testing. They wanted the educational establishment make “explicit the structures of assessment arguments, the elements and processes through which they are instantiated, and the interrelationships among them.” And he agreed with as another ETS colleague and friend the distinguished researcher Michael Kane who once pointe out “there are limitations to a claim, misadventures that can result when we extrapolate from a claim.” Bob understood that and throughout his professional life kept trying to get us to be more enlightened and innovative in our thinking about assessments. He spent years looking at how games and simulations might yield more useful evidence for particular claims about what someone knew or could do. He wrote that:

“Advances in cognitive and instructional sciences stretch our expectations about the kinds of knowledge and skills we want to develop in students, and the kinds of observations we need to evidence them (Glaser et al., 1987). Off-the-shelf assessments and standardized tests are increasingly unsatisfactory for guiding learning and evaluating students’ progress.” He was a pro-learning guy, not necessarily a pro-testing guy.

In fact he cared about helping the opt out movement and the anti-testing ‘memers’ better understanding the nature of a claim. He told me that they would be advantaged in what they really cared about – the welfare and flourishing of their children — if they had this knowledge so that they could then go to their schools, to the superintendents, to the teachers, to their politicians and say, ‘you need to make better claims about our children. You are misusing the educational measurement system.’. T.

Bob used to emphasize to me and others that it’s going be very different to assess whether somebody can do some sort of physical task as opposed to assessing whether they can analyze the situation as opposed to assessing whether they could be an air traffic controller. He made sure we keep in the forefront of design discussions that the type of claim that we’re making their will differ in both the static or dynamic nature of the language, the amount of other skills that are interdependent upon it, the amount of other independent variables. The circumstances in which somebody would then have to apply their knowledge makes for differences within the claim. But in every case Bob patiently reminded us to follow the sequence of identifying the claim we want to make and then look at what tasks would provide evidence that would allow us to assert that this person can do those things or does know those things.

He was ahead of us all when it came to thinking of new ways to get the best evidence to allow us to know what our students were ,earning. “Opportunities borne of new technologies, desires borne of new understandings of learning—a new generation of assessment beckons. To realize the vision, we must reconceive how we think about assessment, from purposes and designs to production and delivery.”

He became very involved in that realm that both inspired ECD and has informed it: games and their possible connections to assessment. Assessment design is compatible with game design, because they build on the same principles of learning. In a book chapter, he co-wrote with some colleagues from Cisco and other organizations, “Three Things Game Designers Need to Know about Assessment, Evidence Centered Design for Game-Based Assessments”, one of those things is stated as “Assessment design is compatible with game design, because they build on the same principles of learning.”:

When we design a game or assessment, we are determining the kinds of situations people will encounter and how they can interact with them.

The art of game design is creating situations, challenges, rules, and affordances that keep players at the leading edge of what they can do. Serious games do this so that what players must learn to do to succeed in the game are important things to know and be able to do in a domain such as genetics, history, network engineering, or land use planning.

The art of assessment design is creating situations such that students’ actions provide information about their learning, whether as feedback to themselves, their teachers or a learning system, or other interested parties such as researchers, school administrators, or prospective employers.

Each of these considerations for a game or an assessment imposes constraints on the situations we design and what can happen in them. Game-based assessments need to address them all at the same time.”

I could go on: Bob Mislevy’s impact in so many areas was immense, and I have not even touched upon his extraordinary openness and mentoring. The world was better for Bob being in it. That is what we all aspire to attain, and he did so. Rest in peace.