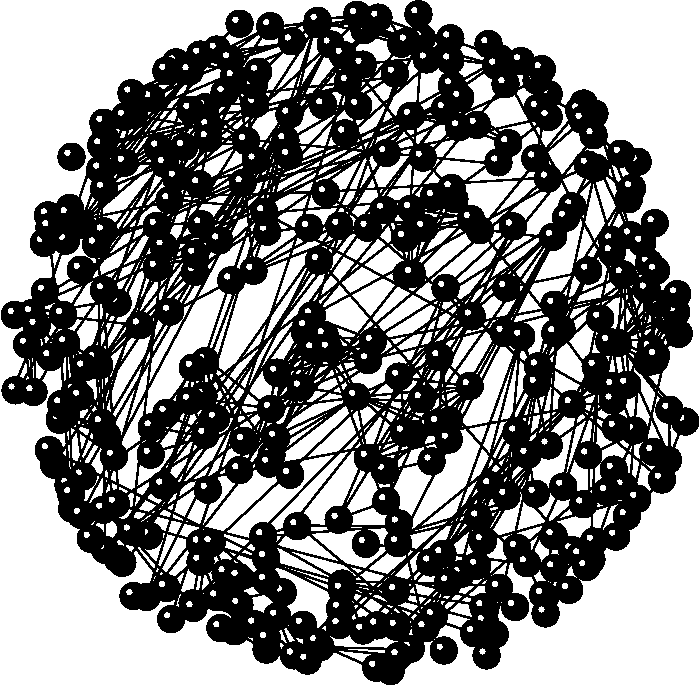

SOURCE: SEMI Semiconductor Industry Genealogy Chart.

You cannot teach an old dog new tricks. Or is it possible that the saying really should be that venerable canines like your correspondent cannot unlearn their old tricks? This conundrum confronts me almost daily as my neural tentacles quiver at the sight of some factoid or phrase they were trained to retrieve — and rewarded for retrieval — over decades of my motley career. (The tentacles are metaphorical, of course, the only tentacles creeping out from my form are the stray whiskers of my unruly latte white beard.) This training of my mind with a mere scan of an obituary in the New York Times can hurl me back into my personal history of testing, into another consideration of the ways in which we get educational measurement wrong.

The word testing never appears in the obituary of Christopher Meyer. Instead, its connection to that world is through a testimony to ways in which testing’s power is overestimated and misrepresented as the pathway or gateway or blockade to success in this world.

Meyer was the British ambassador to the United states during a crucial era: 09/11 and the second Iraq war. He later wrote books and “also hosted television documentaries, including a BBC series, “Networks of Power” (2012), in which he sought to identify the attributes that powerful global cities and their influential inhabitants share.”

Aha! Meyer must end up discovering through this research that what really mattered in getting to the top in those societies was the test scores of potential leaders. Or did he?

“I thought, this is really interesting — what makes these cities tick? Who makes them tick?” he told The Guardian in 2012. “And I started off with a hypothesis, which I think has been more or less justified by the filming, which was: Perhaps they have more in common with each other than they do with their own countries. Having watched Mumbai, Moscow and Rome, I would say the common trait is an alarming degree of nepotism.” (Emphasis gleefully, indulgently, and self righteously added.)

The complaints that testing regimens obstruct the ability of individuals to gain admission to important decision making roles in our institutions miss this point. It’s not solely about what you know and perhaps not even importantly about what you know as long as you can make up for it substantially with who you know. And if who you know is someone who is related to you so much the better.

As Meyer further noted, “it is your nature to surround yourself with people who you think will advance your interests, with whom you have some essential compatibility, and with whom you get on.”

We don’t have to rely only upon the testimony of someone as savvy and well traveled as Christopher Meyer to prove the power of relationships over the influence of testing There are significant research studies regarding powerful networks. Consider Silicon Valley and this study by Castilla, Hwang, and the great Granovetters.

“A “social network” can be defined as a set of nodes or actors (persons or organizations) linked by social relationships or ties of a specified type. A tie or relation between two actors has both strength and content. The content might include information, advice, or friendship, shared interest or membership, and typically some level of trust. The level of trust in a tie is crucial, in Silicon Valley as elsewhere. Two aspects of social networks affect trust. One is “relational”—having to do with the particular history of that tie, which produces conceptions of what each actor owes to the other. The other is “structural”: some network structures make it easier than others do for people to form trusting relationships and avoid malfeasance. For example, a dense network with many connections makes information on the good and bad aspects of one’s reputation spread more easily”

And what do these networks do? They prize prior relationships; they privilege memberships in certain castes of American society.

The authors found that networks underlie the success of regions for a variety of industries. That is not to say that testing is completely without influence. The networks draw upon higher education institutions and certain higher education institutions such as the Ivy League colleges, Stanford, Caltech, Duke, U Chicago etc play important feeder functions to the networks. In many instances, test scores did allow people to get into those higher institutions but as previously pointed out in this blog, many people ended up in those exclusive colleges without the highest test scores.

Again, confirmation bias is sitting on my shoulder as I write this. layers of indignation at the commentariat’s ignoring of the ways in which people actually get into positions of authority coat every word I write on this subject. That’s why I would love for someone to disagree with me, to enlighten me as to what I am missing in this argument. And now, this old dog is going to go lie down.

Sorry, T.J., but I can’t disagree with you on this one! As someone who has noodled around the edges of ‘the elite’ for decades, I can absolutely confirm your confirmation bias with my own. But equally, I recognise that I’m part of a different caste of ‘elite’ for others… I don’t think I have any answers. Perhaps it is down to any individual who is not ‘in’ the elite not having a chance of understanding its power and potential until it is way too late to do anything about it. It’s too late for me to break into ‘the elite’, it was too late even when I went to university the first time, I simply didn’t go to the right schools, and I wasn’t born into the ‘right’ family… It isn’t the academic testing that’s the issue, it’s the background checks!

A look at various worlds — politics, finance, edcuation — only confirms our view: networks provide substantial advantages.