Over the Christmas week as is our custom, my wife, Marjorie, and I watched several favorite movies. The winner for most viewed film during our more than four decades together has to be The Philadelphia Story even though the story itself contains elements that make us just a little bit more uncomfortable as each year passes. (The rich folks get off a little TOO easy.) What delights us is a collection of performances that sparkle even on the umpteenth viewing. Watching Jimmy Stewart get drunk and then drunker and finally drunkest charms us just as the ‘inside Hollywood’ stories tell us those theatrics charmed his costars Cary Grant and Katherine Hepburn. For those of you who don’t know this tale, Stewart’s character is a reporter whose unscrupulous editor has placed him in a society wedding due to a sort of blackmail. At one point, well in his cups and after having hiccuped egregiously in Cary Grant’s face, Stewart’s reporter plots his revenge against the editor.

“Let me tell you about the time he went to Boston…to be awarded the Sarah Langley Medal for World Peace. The true story on that little jaunt would ruin him.”

Emphasis added

Emphasis added because those two words — true story — always catch our attention. In this case, the phrase strikes the ear with particular weight because we sense that up until now there’s something that we haven’t learned that will change the way we see the world even in a comedy like this one. The true story will illuminate the reality of the situation. What also strikes us here is that the true story will be one that delivers a comeuppance to those who deserve such a fate.

In this series of 31 consecutive daily posts about testing, one purpose pursued is to convey some of the realities of testing in order to persuade others of its value in the time of concerted campaigns to denigrate or eliminate it while also illuminating its deficits that need correction. What difference does it make to tell these stories and to get others to tell their personal histories? Awareness stands as a necessary precondition to any change. And anything that can be done to raise awareness as to the realities of a dimension of our lives that affects all of us immensely and has the potential to do so much more good than it currently accomplishes seems to me to be a good thing. Part of my reality of testing is that the majority of the American public fails to understand what should be, what usually is, and how they might influence its presentation in daily life. Whether this blog will succeed in its purpose or not, time will tell.

Meanwhile, on with telling…

Unlike the Jimmy Stewart character, I’m not interested in unveiling some true story that I witnessed during my time at the world’s preeminent educational measurement organization in order to settle some score. But biases exist in my sense of the reality of testing.

When it comes to testing, each one of our personal histories is a true story. In the sense that physicist David Bohm asserted in 1977 about the word true:

“Reality is what we take to be true. What we take to be true is what we believe. What we believe is based upon our perceptions. What we perceive depends on what we look for. What we look for depends on what we think. What we think depends on what we perceive. What we perceive determines what we believe. What we believe determines what we take to be true. What we take to be true is our reality.”

Reality isn’t all it’s cracked up to be

Dietrich Dorner influenced my brother John Elliott and I significantly when we wrote Decision DNA over twenty years ago. In his book The Logic of Failure, Dorner writes, “A person’s model of reality can be right or wrong, complete or incomplete. As a rule it will be both incomplete and wrong and one would do well to keep that probability in mind.”[i][

With that caveat of my reality suffering both of those flaws, let me offer a pair of realities observed during my time in the belly of the testing beast:

#1 Testing in the United States for the most part is not about the test-taker.

#2 Measurement is imperfect and experts in measurement know that.

Let’s start with # 1 and introduce the notion of a warrant in testing. #2 will appear as tomorrow’s post

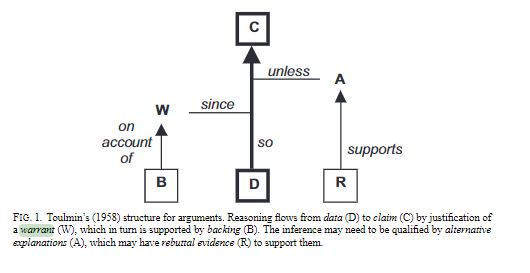

Bob Mislevy in his excellent paper Substance and Structure in Assessment Arguments defines and contextualizes a warrant in this paragraph drawing upon “Toulmin (1958) provided terminology for talking about how we use substantive theories and accumulated experience to reason from particular data to a particular claim.” The figure below “outlines the structure of a simple argument. The claim is a proposition we wish to support with data. The arrow represents inference, which is justified by a warrant, a generalization that justifies the inference from the particular data to the particular claim. Theory and experience, such as empirical studies and prior research findings, provide backing for the warrant. In any particular case we reason back through the warrant, and qualify our conclusions if there are alternative explanations for the data.”

Got that?

You want to say something about somebody. Think driver’s license. That’s the claim. You’re going to collect data specific to what you want to say about that person. You might get the data by watching them and writing down your observations or by giving them some tasks to do and noting their success or failure in completing those exercises. Think road test and written test for that license. But just to make sure that your whole enterprise isn’t some ‘one-off’ weird notion (think making your test-taker compete in a ‘demolition derby’, you ground this whole method of choosing certain data to allow you to make an inference to support a particular claim in a warrant, “a generalization that justifies the inference from the particular data to the particular claim.” In other words, you’re not the first person to make this claim in this way. You rely as Bob notes upon “Theory and experience, such as empirical studies and prior research findings” in order to justify the warrant. “ Warrants “are the “glue” that hold evidentiary arguments together as Schum noted. But…

One of the realities of testing as I observed its formation and operation on a large scale: the true warrant to make particular claims comes from an institution. The warrant for the claims made by the College Board regarding their examinations comes from the colleges that serve on that literal board. Did you know that the College Board, originally College Entrance Examination Board, is actually an association of over 6000 universe trees, colleges, schools, and other educational institutions? Thank you Britannica.com. The inferences that scores on those tests translate into claims about how someone will do in higher education arise from a warrant provided by that institution. The same is true of the Graduate Record Exam (GRE), GMAT, and any other big exam you know. Additionally, exams for certification or licensure as a doctor, accountant, lawyer, pilot, and other professions have the same relationship: there’s a big institution that decides the warrant, the generalization that justifies the inference from the particular data to the particular claim. Therefore, the testing entity has first and foremost as its client the institution hiring it to do the testing. ‘First and foremost’ is a cliché, but as Terry Pratchett, wrote in Guards! Guards! “The reason that clichés become clichés is that they are the hammers and screwdrivers in the toolbox of communication.” This particular hammer is useful here because it reminds us that no matter what else is going on the human being taking the test is secondary to the enterprise.

I would expect substantial pushback to this notion, and in the spirit of making arguments ask you to consider this snippet of data: have you ever been asked after taking any of the above tests your opinion as to how the test might be improved? Have you been treated as the client? The institution certainly gets that attention and deference. This is not to say that testing organizations don’t care about the individuals who take their assessments. My experience is that they care a great deal about them, but the point here is that the reality of testing is that the ultimate power resides with the institution. In some cases, such as when a coalition of parents – mostly mothers — managed to scuttle standardized testing in elementary schools their success only stands as the exception that makes the rule. That this cohort of passionate parents were able to succeed strikes us as notable because the rule is that bureaucrats in state Departments of Education are the ones who decide what gets tested, how, when, and by whom.

If test takers were ‘first and foremost’, then tests would prove more useful to them, wouldn’t they?

That would seem to be more than enough controversy for one post. We will return to some other observations about the reality of testing in tomorrow’s post, January 5. True story.

[i][i] Dorner, D. The Logic Of Failure, p. 42

Completely agree that the truth for the test-taker is always different to that for the test-setter and the test-marker etc etc etc, all the way up to the Secretary of State for Education, via the test-taker’s teacher, their parents, their prospective university department… This multiplicity of truths echoes the multiplicity of test purposes identified by Paul Newton (https://doi.org/10.1080/09695940701478321) – it depends on who’s asking! And I cannot recall ever being asked what I thought of an assessment as a test-taker, but I do ask my students what they think about the range of assessments they experience as my students – but they are relatively small groups of post-qualification teachers undertaking substantial professional development, so it is perhaps an easier arena to seek such feedback and evaluation. Completely agree that the truth for the test-taker is always different to that for the test-setter and the test-marker etc etc etc, all the way up to the Secretary of State for Education, via the test-taker’s teacher, their parents, their prospective university department… This multiplicity of truths echoes the multiplicity of test purposes identified by Paul Newton (https://doi.org/10.1080/09695940701478321) – it depends on who’s asking! And I cannot recall ever being asked what I thought of an assessment as a test-taker, but I do ask my students what they think about the range of assessments they experience as my students – but they are relatively small groups of post-qualification teachers undertaking substantial professional development, so it is perhaps an easier arena to seek such feedback and evaluation.