The Uses of Argument by Stephen Toulmin, a foundational text of modern assessment design, the science behind the making of tests, lays out the components of a formal argument that leads to a claim. (And remember the whole reason to have a test is to be able to make some claim about what someone knows or can do.) Toulmin notes that a claim is a “conclusion whose merits we are seeking to establish.” The facts offered “as a foundation for the claim” are our data. But in making a claim we need more than just data, we need some sort of framework upon which everybody agrees to interpret the data. This framework or proposition is what Toulmin calls a warrant. The warrant and its backing provide the rationale or generalization for grounding the claim in the available data. The warrant establishes “the credibility, relevance and strength of the evidence in relation to the target conclusions.”

All of us saw so many cop shows and movies over the years that we were familiar from a very early age with the general meaning of the term warrant. There’s usually some bad guy needling the tough cop by claiming that there is no warrant for search of his premises where he is hiding guns, drugs, bodies, or all of the above. In that case, and in testing, a warrant is a guarantee that everything is on the up and up, that there is some authority behind the particular conclusion. One of the specific meanings out of the Oxford English dictionary for a warrant is “Justifying reason or ground for an action, belief, or feeling.” So whether it is a justifying reason for arresting someone or a justifying reason for saying that your score on the written part of the drivers test means you should go ahead and take the road test, a warrant is the backbone of a claim. The warrant for the SAT came from a bunch of colleges who formed the College Board. That’s true also for the GRE.

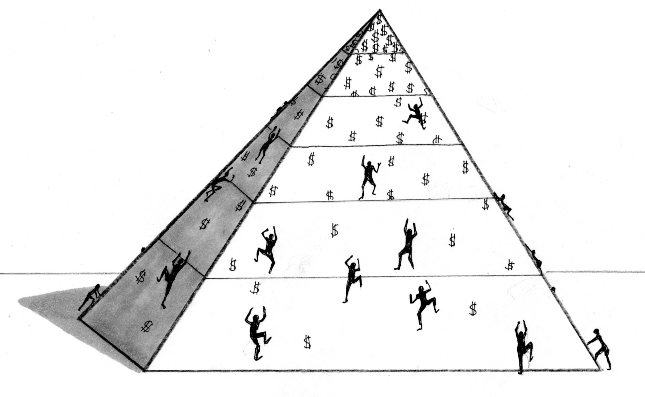

But who issued the warrant for the oft repeated but rarely question claim that America is a meritocracy and that testing is the prime vehicle by which individuals enter the higher reaches of that structure? This commonly held yet wildly mistaken belief stands as an obstacle to any rational and productive view of how testing can and must be a part of education. (As stated previously and as will be stated again in my conclusions a week from today, I am NOT talking about the kind of tests most frequently deployed right now, but rather tests that include alongside literacy and numeracy different elements such as conscientiousness and hope and tests that are always formative in that they tell people how they can get better at whatever is being tested whether it is English grammar or nuclear physics.)

Almost five years ago, Jo Littler wrote a superb article in the Guardian that referenced the beginnings of the term meritocracy. Obviously, if we want to know what the warrant is that allows someone to claim that a system is meritocratic going back to the originators of the term makes sense. While the Oxford English Dictionary defines the term as meaning “…the holding of power by people chosen on the basis of merit (as opposed to wealth, social class, etc.)”, the first two people to coin the term emphasized some other aspects. As far as anyone can tell, the first use of meritocracy came “in 1956 in the obscure British journal Socialist Commentary.” (What? You don’t subscribe?) The writer was a socialist sociologist, Alan Fox, used meritocracy to describe “the society in which the gifted, the smart, the energetic, the ambitious and the ruthless are carefully sifted out and helped towards their destined positions of dominance.” . Two years later, in what became the more famous early application of the term, Michael Young wrote a whole satire about what life would look like in the future under a meritocratic system. he thought meritocracy would be a bad thing.

Littler in her book on the subject “traces the dramatic U-turn in meritocracy’s meaning, from socialist slur to a contemporary ideal of how a society should be organised.” Along the way with help from American sociologist Daniel Bell, meritocracy came to be thought of as a good thing. And then Michael Dunlop Young, author of the original The Rise of the Meritocracy (and by this time also sweetly for those if us who like our irony already cooked Baron Young of Dartington), offered retrospective comments as he observed meritocracy being enshrined as the summum bonum in the Tony Blair political world:

“It is good sense to appoint individual people to jobs on their merit. It is the opposite when those who are judged to have merit of a particular kind harden into a new social class without room in it for others.“

A fair criticism by the Baron, but where did his criticism of a system that he never wanted to see happen leave meritocracy as a concept? Its definition was never nailed down and its existence never validated. That’s understandable because what is described as meritocracy is often hidden from the public; how many citizens know the names of the governmental and corporate bureaucrats who issue and enforce the rules that shape ordinary life in our country? And the leaders that we can see present a very mixed picture of what might be merit: without any political aspersions I offer the following names as examples — Boris Johnson… Oh, why bother going on after Boris? You get the point. There is no body like the College Board or the American College of Physicians or the New Jersey State Board of Cosmetology and Hairstyling issuing the warrant that says this is what constitutes meritocracy.

So what is the framework to pinpoint the kind of data that supports the notion that a) we have a meritocracy and b) people who do well on tests and up in the top tiers of that select priesthood? Where is the warrant for meritocracy that it exists at all in a particular fashion?

On warrants, Michael Zieky, one of the great explainers of assessment and tests and tests, notes that: “When there is a great difference between the observed behavior and the claim that is to be made, the warrant must be comprehensive and convincing.”

Another friend and former colleague who knows so much more about assessment than not just me but almost everyone wrote to me about an article by Adrian Wooldridge promoting meritocracy and Wooldridge’s book on the subject: “As I see it, the problem with this view (of Meritocracy) is that it assumes that merit is unambiguously defined and measured. In his own age, many of Lincoln’s contemporaries though he was a country bumpkin, even among the northern elites, who was totally unqualified for any public office, and everyone thought that McClellan was an ideal general, that Grant was a falling-down drunk. Who gets to decide what merit is?

Conversely (and controversially), should we categorize the Nazi regime in Germany as a meritocracy? Many of the people at the top had advanced degrees. For example, consider this a horrifying, disgusting evil example: the men who met in January of 1942 to devise the final solution were senior civil servants or party officials according to a recent report in the New York times. “Most of them were in their thirties, nine of them had law degrees, more than half had PhDs.” The highly educated and socially exclusive German government bureaucracy simply added agreement with Nazi sympathies to its list of qualifications for leadership. Obviously, the definition of ‘merit’ in such a circumstance does not include its original meaning in the English language of “The quality (in actions or persons) of being entitled to reward from God.” Those guys are all in Hell.

Who gets to define merit then? Some smart observers just assume that the definition is already settled by dint of existing mechanisms and systems. This is where testing is implicated mistakenly; if a meritocracy is bad then testing must be bad as well. Some of the supporters of meritocracy compound the mistake by assumption that court decisions about who gets the top are based on relatively objective determinations of potential value as signaled by someone’s test scores and subsequent academic achievement. “The better the world is at measuring value, the more demanding a lot of career paths become,” Tyler Cowen wrote in his book Average Is Over suggesting that companies and managers will become overwhelmingly precise at measuring ‘economic value’, and decisions about jobs will depend upon those measurements. Maybe these kinds of measurements will happen through smart machines, big data, and other affordances (indeed, are happening today) but that still begs the question of what merit is. I mean the machines have to start somewhere. And the definition setting of the construct is currently beyond their capacity. Test-makers facilitate the making of claims that relate to the prospective addition of value, but they do so specific to a particular construct that may not be generalizable to larger or long-term success.

Simply choosing those were already at the top would not work in the long term either. Many a corporate leader has proved successful by the measures of stock-price performance and popular acclaim only to stumble and even collapse when the realities of the world have a longer time to do their work.

Cowen admits that, this “coming world of hyper meritocracy… is not necessarily a good and just way for an economy to run.” But he is just as clear that he expects it to take place nonetheless: “the world is demanding more in the way of credentials, more in the way of ability, and is passing along most of the higher rewards to a relatively small cognitive elite.”

I will agree that the elite is relatively small, but I refuse to agree that their ‘eliteness’ is all about cognitive aspects. Again Boris Johnson. But this time let me add Travis Kalanick of Uber and the WeWork CEO Adam Neumann along with a list that is pretty long of CEOs who made some pretty stupid decisions. In considering that list we are still left with the difficulty of defining what the merit of meritocracy actually encompasses. Each one of them pretty much ended up rich, but along the way the question of whether they possessed merit was answered with a rather resounding no whatever merit is.

An important example of the characteristically fuzzy use of the word — actually, ten examples — appeared recently when The Chronicle of Higher Education asked ten scholars to weigh in on the questions of whether meritocracy “stalls social mobility, entrenches an undeserving elite, and undermines trust in higher education.” Almost none of the commenters referenced in their replies what Young originally defined as a meritocracy. But two of them — Agnes Callard and Lauren Schandevel — hit important marks. Callard unsurprisingly as one of America’s leading philosophers asks us to make an important distinction between two different kinds of meritocracy: “timocracy”, which “focuses on bestowing honors for what was done” and “technocracy”, which seeks to “discern the talent that predicts future contributions.” Even with those distinctions, Callard notes that “What makes meritocracy such an easy target is that we will always be able to complain either that someone didn’t earn what they received, or that they were not the best person for the job.” And that’s the point: there is no meritocracy because there are many people in the top tier who did not earn what they received or were not the best person for the job by any plausible definition of the word ‘merit’.

Schandevel charges that meritocracy is a myth and that the better term for the upper tier of our country’s hierarchy is oligarchy. The ticket for admission to that group is social capital that Schandevel perceptively notes any aspirant will “need to maneuver their way through elite spaces and to signal to others that they belonged there.” If we were in a meritocracy, then those in the most desired positions, the wielders of power, the makers of decisions, would be those with the most worth, those entitled to reward, not those with the strongest and most influential networks. I don’t know if a meritocracy in the United States of America ever existed, but even the most cursory examination of those at the top shows its absence today.

Social capital is about “the value of social networks, bonding similar people and bridging between diverse people, with norms of reciprocity.” It usually favors people who are similar to the existing members of the network. Those tightly knit networks are often fed by family or friend affiliation. Avi-Asher Shapiro depicts the reality of a particular peak of the governance of the world in which we live plainly: “From its earliest days, venture capital mirrored, and amplified, the core structural dynamics in the American economy: What often counts most is who you know, and who your parents are.” And if your parents have money, so much the better than merit in getting to and staying at the top of the structure.

The importance of wealth and family connections are what critics of meritocracy like Thomas Franks neglect while admitting that there is a hierarchy, but insisting that it is one of “merit, learning, and status”… a ‘progressive’ view of social hierarchy in which talent and ability are the natural arbiters of who should rule in a society.” Michael Sandel in marking an eloquent populist complaint about the tyranny of merit, obscures that the issue really is about the tyranny of power, of decision-making rights. The game is rigged but the education signals and other glittering prizes the elite flourish are just the outer trappings of a rotten system. If we wish to rebuild the civic infrastructure of shared public life as Sandel suggests, then we must start with an accurate picture of the current infrastructure, hierarchies based not on merit but on other forms of power. Yes, those who excelled on tests and came out with the cum laudes rose up on the ladders of responsibilities and rewards, but they are nowhere near the top rungs in most cases unless they also possess some form of this capital. Hunter Biden deserves credit for his frank admission that “I don’t think there’s a lot of things that would have happened in my life if my last name wasn’t Biden.”

The problem of definition might be easily remedied, if the decriers of meritocracy simply used ‘find and replace’ functions before hitting ‘share’ on their offerings. For example, with that replacement the conclusions of Richard Reeves (whom I much admire) steer us to a clearer depiction of the complex problem that society faces. Just substitute the word oligarchy for the word meritocracy in the following paragraph: “(Oligarchy) thus justifies and amplifies material inequality, by weakening the foundation of mutual respect needed for the funding of public goods, or support for greater resource-redistribution. The ideology of (oligarchy) is the connective tissue between material inequality and relational inequality.” Bernie Sanders was correct five years ago when he wrote that we had slid toward an oligarchy, which as Matt Simonton reminds us using Ancient Greece as a model “should not be seen as a stepping stone on the way to democracy, but rather as a reaction by elite regimes against the threat of democratic revolution.”

Perhaps more accurately, we have a ganglion of oligarchies that support and reinforce each other.

Calling it so allows us to address what Irwin Kirsch and Henry Braun termed the growing opportunity crisis resulting from “the accumulation of advantage or disadvantage experienced by one generation (to be) increasingly passed along to the next. As a result, life outcomes are increasingly dependent on circumstances of birth.”

Calling it an oligarchy highlights the locations of its members and prevents the evasion of the fact that as Douglas Massey and Jonathan Tannen found “residential segregation is the structural linchpin of America’s system of racial stratification.” Demographics is destiny. If you don’t change the demographics, then the test or whatever mechanism you use as a gate to some experience or opportunity will not make a difference.

Calling it an oligarchy gets at the way in which almost all of its members look alike. Even if people of color — especially Blacks and Latinos — get high scores and ivy degrees, they still operate within less powerful networks as documented by Rochelle Parks-Yancy. And societal pressure that they prove themselves in one particular domain makes it more likely that they will be specialists rather than generalists, which again causes a lower likelihood that any of them ever get the CEO job. That loss is a difference that makes a difference because CEOs hire future CEOs and generate their own social capital through powerful networks.

The sociologist Daniel Bell whom Young quoted approvingly in that 1993 introduction, once wrote that, “Conceptual schemes are neither true nor false but are useful or not.” Meritocracy as a concept is not useful now; it only confuses. Whether we are talking about Hunter or Eric, Yvonne, or Chelsea, referencing meritocracy camouflages intransigent issues of race, class, and wealth. If we put it aside, we stand a better chance of defining the problems in such a way so as to discern possible solutions. All systems resist change and complex systems resist change in complex ways. What I know is that continuing to mistake the nature of the system enables the system to stay just the way it is.

There is no warrant for meritocracy as so often defined and the disconnect with the people who actually did the best on various tests is apparent. More on that aspect of the disconnect between meritocracy and testing tomorrow.

#bloganuary

Talking of merit, don’t we all deserve to be above average in all tests? Oh, no, oops, that is mathematically impossible…